The idea was conceived while sitting at a table drinking coffee and chatting about a recently released request for proposals funded by USAID (United States Agency for International Development) to conduct international studies in Feed the Future* countries.

We and two Ph.D. students from Kenya saw a unique opportunity to bridge the expertise from the University of Wyoming and research and extension capacities in Kenya and Uganda.

A few months later, Jay Norton led a group of scientists from the departments of ecosystem science and management, plant sciences, and agricultural and applied economics in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, and from the College of Business, with collaborating universities and non-governmental organizations from Kenya and Uganda. The group received $1.85 million for what the reviewers described as “The most out-of-the-box idea.”

The now-completed, five-year study assessed the effects of adopting conservation agriculture (CA)-based strategies by small-holder farmers in the border region of Kenya and Uganda in many unique ways with the legacy reaching far and beyond the duration of the project.

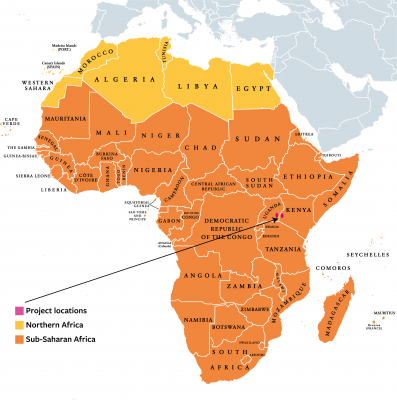

Sub-Saharan agriculture

Small-holder farmers are predominant in sub-Saharan Africa, the region south of the Sahara Desert. They farm less than 1 acre and grow maize (Zea mays L.) intercropped with common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on heavy, weathered, and nutrient-poor soils by using deep (to a 10-inch depth or more) inversion-type tillage.

Small-holder farmers are predominant in sub-Saharan Africa, the region south of the Sahara Desert. They farm less than 1 acre and grow maize (Zea mays L.) intercropped with common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on heavy, weathered, and nutrient-poor soils by using deep (to a 10-inch depth or more) inversion-type tillage.

Animal-drawn plows and hand hoes invert the soil. Frequent deep tillage causes significant declines in soil fertility and crop yields. Weed competition is also a serious problem, and using tillage for weed control has not been very effective.

In addition, Mt. Elgon Highlands have a bimodal pattern of precipitation characterized by long and short rainy seasons. Crops are grown during one long growing season in the cooler, higher-elevation parts and during two growing seasons (long and short) in the warmer, lower-elevation areas. Year-round cropping and inversion-type plowing have resulted in soil degradation, increasing yield gaps and the overall major threat to sustainability of local farming and food security.

Adopting conservation agriculture strategies has become a necessity rather than a choice given projected increases in human population in the sub-Sahara.

CA strategies focus on reducing soil tillage, retaining post-harvest crop residue, and the inclusion of dinitrogen (N2)-fixing cover crops in crop cycles.

Although successful in many parts of the world, small-holder farmers in this region have had mixed successes. Limited adoption was largely caused by slow realization of the benefits associated with soil health during the first few years of the transition and limited understanding of the intermediate and longer-term advantages, especially weed control practices.

Transition from conventional to conservation agriculture

This project assessed environmental and socio-economic outcomes of CA practices using research tools that rely on farmer-researcher co-design and co-innovation. We wanted to evaluate the effects of transition from conventional maize/bean intercropping to CA tillage and cropping systems on weed populations, maize growth, and management costs.

We hypothesized reducing tillage and rotating maize/bean intercropping with cover crops would result in soil health improvements and declines in weedy species populations with no negative effects on maize performance.

The project was deployed at four locations around Mt. Elgon: two on the east side of Uganda and two across the border in western Kenya. Out of each two, one site was at the highlands (one long growing season) and one at the lower elevation, where farmers are able to grow two crops per year.

Cropping systems consisted of a series of scenarios that included cover crops in typical maize-bean intercropping. Specifically, mucuna (Mucuna pruriens (L.) DC.) was relayed in maize and planted in maize interrows following bean harvest or planted in a strip-intercrop arrangement in which maize, beans, and mucuna were grown in monocultural strips narrow enough for advantageous interactions such as light interception and complementary root growth. Each system was planted using three tillage approaches: conventional moldboard plow, minimum tillage, and no tillage.

Understanding weed response during transition

This study suggested introducing minimum till and no-till resulted in immediate declines in weedy grass and forb populations. Not only did the overall grass and forb cover decline, but the most notorious weeds showed significant reduction. Reductions in weed density, however, were more pronounced at the higher elevation site, where crops are grown during one long growing season and managed with fewer tillage operations.

Greater declines in weed density in response to reduced tillage rather than new cropping systems confirmed to us that the effectiveness of using cover crops to control weeds may become evident later in the transition. Reduced- and no-till approaches became viable options in socio-economic settings in which farmers have access and capital to purchase herbicides.

Alternate tillage approaches are also viable in areas where reducing tillage did not negatively impact crop production due to, for example, high accumulations of clay in the sub-surface soil horizons. Costs of manual labor, however, should be considered in relative terms, as some of the work was usually performed by family members, reducing the overall cash flow outside of the household. A combination of reduced tillage and herbicide use may bring the most desirable effects.

Soil health improves

Conservation agriculture practices improved soil health within the first five years. Our observations revealed greater soil organic matter loss and lower yields in regions where crops were grown during two seasons per year compared with one long growing season.

Growing crops during two growing seasons required more frequent tillage and resulted in shorter periods of soil rest. High soil organic matter mineralization with low plant residue returns and low overall yields suggested that continuing typical crop production in this region may ultimately become more challenging and unsustainable.

Small-holder farmers at lower elevations were in economic need to grow crops during two growing seasons; the alternative adoption of fallowing the land during short rains might limit success. Other alternatives may include government-supported incentives. Since the incidence of crop failure during short rains at low elevation was likely to become more frequent, focusing efforts toward one-season crop production during long rains may also be of value to farmers.

Conclusions and considerations

In general, the lack of immediate increases in farm income while transitioning to CA has been often associated with reduced success of CA adoption. Evidence suggested during the initial period of transition that declines in crop yields could discourage small-holder farmers from continuing and was driven by an inability to support family and generate income.

Since small-holder farmers generally value short-term returns more than long-term benefits, practices that reduce investments in labor and, ultimately, require fewer chemicals to combat reduced populations of weeds became beneficial. Better understanding of herbicide use, availability at local distribution outlets, and smaller packaging aided adoption of alternative tillage by smallholder farmers.

CA needs to cater to local climate, soil resources, and structure of the needs of the farmers. In addition, introducing new N2-fixing cover crops required additional expenditures and reduced the amount of land otherwise allocated to grow food.

Finally, reducing or eliminating tillage also necessitated additional cost investments and replaced manual, family-contributed labor with chemical weed control.

To contact: Urszula Norton can be reached (307) 766-5196 or unorton@uwyo.edu; Jay Norton can be contacted at (307) 766-5082 or jnorton4@uwyo.edu.

*Feed the Future is a U.S. government global hunger and food security initiative (www.feedthefuture.gov).