Most life forms we are familiar with, including plants, animals, fungi, and many single-celled organisms, rely on sexual reproduction to continue their species.

In many organisms, sexual reproduction may appear relatively straightforward. Two parent organisms each produce a specialized cell—like sperm and eggs in humans—that contains half their genetic material. Then, these two specialized cells, also known as gametes, merge together to form the beginnings of a new organism.

But how exactly do those gametes come together and fuse to create new life? That’s what Jen Pinello, an assistant professor in UW’s molecular biology department, set out to investigate.

Surprisingly, her research may also hold the key to preventing the infectious spread of deadly diseases, such as malaria.

Three steps, three proteins

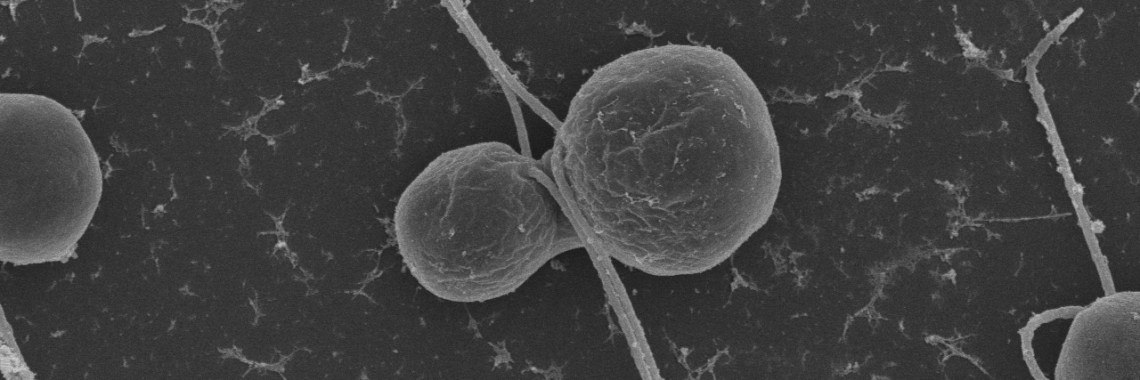

Pinello is studying the proteins and molecular processes of sexual reproduction in a single-celled green alga called Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

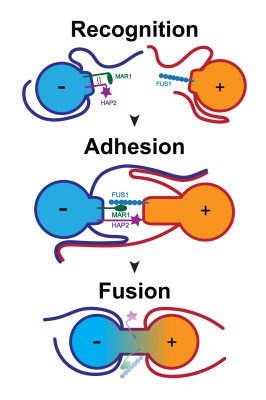

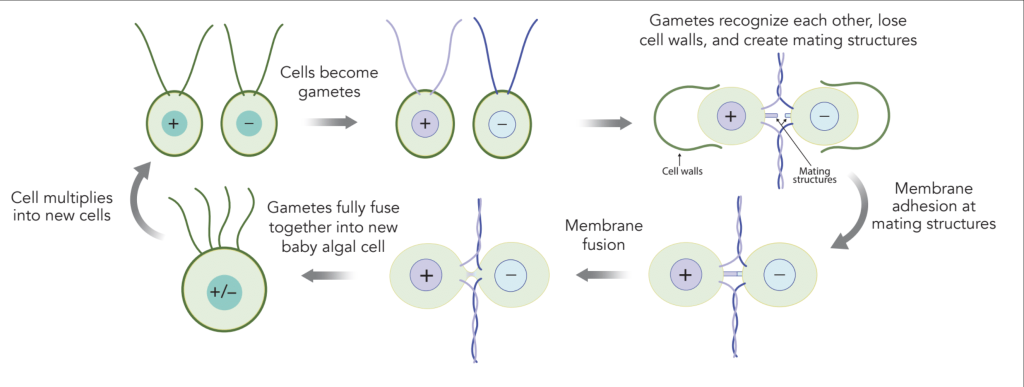

First, the two gametes recognize each other; next, the gametes adhere to each other; and finally, they fuse together. Graphic by Jen Pinello.

All gametes are enveloped in a membrane that separates their cellular contents from the outside world. Like almost all other gametes, Chlamydomonas gametes must perform three steps to successfully complete sexual reproduction: first, they find an appropriate gamete to partner with; next, the membranes of the two gametes adhere to each other; and finally, the two membranes fuse together.

During reproduction, Chlamydomonas gametes rely on three essential proteins—MAR1, FUS1, and HAP2—to adhere and fuse their membranes. If any of these three proteins are missing, Chlamydomonas gametes cannot successfully come together and produce a baby alga.

FUS1 is located on one type of Chlamydomonas gamete (in scientific literature, this type is referred to as +), and MAR1 and HAP2 are located on the other (– type). Once two gametes of these different types have recognized each other, FUS1 and MAR1 attach to each other to adhere the two gametes together. Then, HAP2 fuses the gamete membranes together.

Pinello and her colleagues recently discovered MAR1. This discovery makes Chlamydomonas the only organism so far in which scientists have identified the proteins required for gametes to adhere and fuse together.

Scientists have identified many proteins essential for sexual reproduction in different organisms, but they have struggled to determine exactly what those proteins are doing—or even which step of sexual reproduction (gamete recognition, adhesion, or fusion) they are participating in.

Species-specific proteins

HAP2 is necessary for gamete fusion in many different organisms, including flowering plants, insects, and single-celled parasites—such as those that cause malaria. FUS1 is used by fewer organisms. It’s found only in algae and plants. Finally, MAR1 is only found in Chlamydomonas and other closely related algal species.

Pinello and her colleagues have discovered that after MAR1 and FUS1 proteins adhere two gametes together, HAP2 changes form. HAP2 cannot fuse Chlamydomonas gametes together until it has changed form.

Pinello’s research suggests HAP2’s changes may rely on cues from MAR1 to prevent HAP2 from fusing together gametes of different species.

Other species may have their own version of MAR1. Learning more about how these adhesion proteins regulate HAP2 may help scientists understand reproduction in many kinds of species and perhaps even prevent parasitic reproduction.

“I think what’s great about this work is that it’s got these really basic fundamental findings that are important for understanding reproduction at the molecular level in a wide majority of eukaryotic species, but then there’s also these applied aspects where this research could lead to new strategies to defeat parasitic diseases like malaria,” says Pinello.

Which came first, the virus or the egg?

HAP2 is an ancient protein that was likely present in the very first eukaryotic cells (cells that contain a nucleus where their genetic information is stored).

Pinello and other researchers have discovered that HAP2 has an eerily similar structure to the proteins that some viruses, including dengue and Zika, use to invade cells. To infect organisms, these viruses must first fuse their membrane with that of a target cell. HAP2 is used during reproduction, while these virus proteins are used during infection, but both have the same function: they fuse cell membranes together.

The structural similarities between HAP2 and these viral fusion proteins are very unlikely to be a result of chance, which strongly suggests that these proteins share a common ancestor.

This finding begs the question: did this “common ancestor” protein first help infect other cells, or did it assist with sexual reproduction? In other words, which came first, the viral fusion protein or the egg?

The answer might imply that sexual reproduction originated from a viral infection. On the other hand, perhaps a virus stole its fusion protein from the gametes of a primordial cell.

One way or another, the protein HAP2 has a lot to tell us about how membrane fusion has shaped the evolution of life and disease.

The birds and the bees… and malaria

Malaria is a disease caused by single-celled parasites from the genus Plasmodium. Symptoms of malaria include fever, fatigue, and seizures.

Plasmodium falciparum is one of the deadliest species that causes malaria infections in humans. This species alone kills about 600,000 people annually, most of whom are infants and young children.

In humans, Plasmodium parasites replicate asexually in the liver and red blood cells. When a mosquito bites an infected human, Plasmodium cells are transferred from the human to the mosquito.

Inside the mosquito’s gut, Plasmodium gametes reproduce sexually. When the mosquito bites another human, the next generation of parasites are passed on to another victim.

A new kind of vaccine

Historically, malaria vaccines have only targeted the asexual stages of the Plasmodium lifecycle that happen within humans. The two existing vaccines reduce the risk of a severe infection or death for some, but not all, individuals. Additionally, existing vaccines usually don’t provide complete immunity to the parasite even when they reduce symptoms. This means that even vaccinated people with no visible malaria symptoms can be infected and transmit the parasite to someone else.

A vaccine that targets HAP2 could prevent infected individuals, even those with a mild form of the disease, from spreading the parasite to others.

“It’s time to consider the entire malaria life cycle—sexual and asexual forms—and create a new type of vaccine,” says Pinello. “You have to target at least two different things, one to prevent parasite spread and one to prevent disease in the individual.”

A mosquito that bit a person who had received this new type of vaccine would consume anti-HAP2 antibodies along with its bloodmeal. Antibodies, which act as the guards of the immune system, would stop Plasmodium from reproducing in the mosquito’s gut—preventing the mosquito from transmitting the parasite to any other humans. This could help protect whole communities, including infants, who do not benefit much from current malaria vaccines.

To generate the best possible vaccine against HAP2, one of the first steps is to find which parts of the HAP2 protein are exposed before HAP2 fuses gamete membranes together. Exposed parts of the protein could serve as a target for antibodies.

Pinello’s research on Chlamydomonas reproduction could ultimately help identify these vulnerable sites on HAP2 proteins and inform vaccine design.

This article was originally published in the 2025 issue of Reflections, the annual research magazine published by the UW College of Agriculture, Life Sciences and Natural Resources.