For Alzheimer’s patients and caregivers, late afternoon and evening can be a particularly challenging time. Rather than winding down at the end of the day, people with Alzheimer’s often exhibit increased agitation, aggressive behaviors, and a tendency to wander.

This clinically recognized phenomenon is known as sundowning, and often contributes to the decision to institutionalize patients rather than continue home care.

Disruption of circadian rhythms

Sundowning is highly correlated with phase delay, a disruption in circadian rhythms that shifts the timing of rest periods. Alzheimer’s patients typically go to bed later than peers of the same age without the condition. They also experience the drops in body temperature and locomotor activity associated with resting phases on a later time schedule.

Although both sundowning and phase delay in Alzheimer’s patients are well documented, their underlying causes have remained unclear. But, thanks to a researcher in UW’s Department of Zoology and Physiology, that may change.

A novel neural circuit

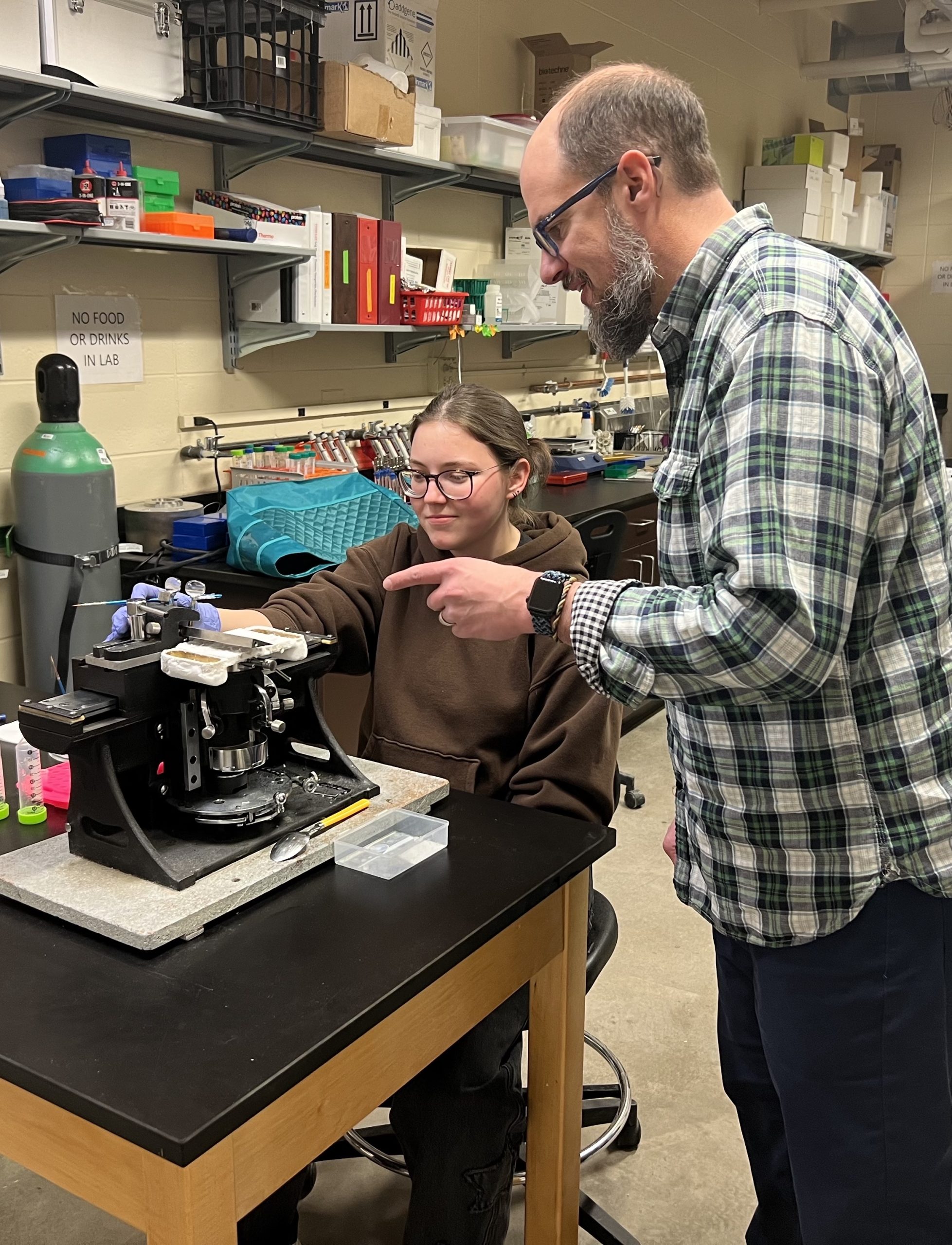

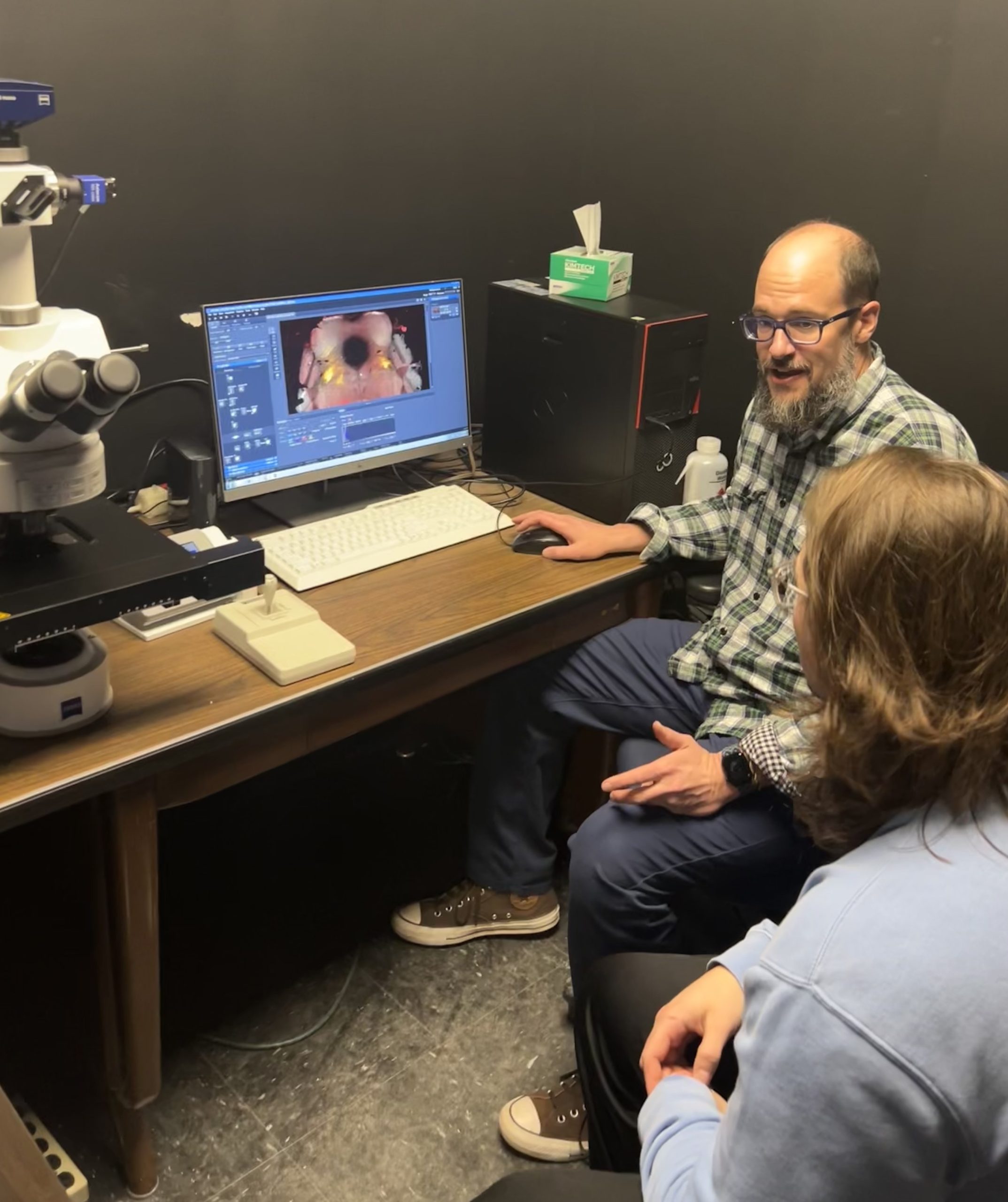

Assistant professor Trey Todd and his lab recently discovered a neural circuit linking an area of the brainstem known to show early indicators of Alzheimer’s disease to the hypothalamus, an area of the brain that regulates circadian rhythms.

Todd didn’t initially set out to investigate Alzheimer’s disease, though he had studied the neuroanatomy of circadian rhythms in mice for years. But, as he examined the neural pathways associated with rhythms like body temperature and sleep phases, he noticed these brain areas also sent signals to an area of the hypothalamus associated with aggressive behaviors.

This observation piqued his interest in sundowning. “In late afternoon to early evening, right when they should be winding down for the day, Alzheimer’s patients can become much more agitated,” he says. “The thought was, given the circuitry we saw, are these people more reactive, and more likely to be agitated at that time of day, because there’s a disruption somewhere in that circuit?”

To test the theory, he first conducted aggression testing in mice at different times in the day. Sure enough, they were more aggressive at certain points in their circadian rhythm.

With further experimentation, Todd determined that disrupting the neural circuit linking the brainstem and hypothalamus triggered heightened aggression at times when mice were usually less aggressive.

Mice with genes mutated to mimic Alzheimer’s pathology were more aggressive at the beginning of their rest phase, a time when they would typically be less aggressive—similar to how Alzheimer’s patients exhibit sundowning symptoms leading up to bedtime.

“It’s not a perfect model, but it’s a way of showing that in an animal with a similar brain structure and pathology, they’re showing similar circadian disruption and are more aggressive at a certain time of the day,” he explains.

Todd also found that increased aggression and circadian dysfunction developed much earlier in female mice than males. Since two-thirds of Alzheimer’s patients are women, this discovery may help researchers better understand why women are more likely to develop the condition.

Practical applications

In 2023, Todd received a five-year, $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to fund further research. Current experiments include inducing Alzheimer’s pathology solely in the areas of the brain involved in the neural pathway he discovered, rather than across the brain. So far, he says, there’s strong preliminary evidence indicating that if Alzheimer’s pathology occurs only in that pathway, phase delay and increased aggression still occur, suggesting the pathway is key to triggering phase delay and sundowning.

Previous studies have shown that people who ultimately develop Alzheimer’s disease may exhibit phase delay and circadian disruption decades before they begin experiencing memory loss. A better understanding of the neural pathways disrupted by the disease may help researchers develop strategies for prevention and treatment of sundowning, potentially easing the challenges faced by caregivers and reducing institutionalization rates.

“If you have people that are at risk for Alzheimer’s disease and you know they’re phase delayed, then you probably also know they’re starting to get pathology in this brainstem area and we need to do everything we can to slow that progression,” Todd explains.

According to a 2022 report by the Alzheimer’s Association, an estimated 6.5 million Americans ages 65 and older suffer from Alzheimer’s dementia. For the most part, treatment is limited to managing symptoms.

Todd’s findings may help change that. “I hope our research may point to methods for earlier detection and interventions that could slow the progression of the disease,” he comments. “Actually knowing the brain areas that might be involved should lead to better outcomes.”

As he continues to study neural circuitry and circadian rhythms in mice, Todd hopes that one day his work will positively impact human patients. “I hope that my research leads to even better suggestions for people who have loved ones who are encountering Alzheimer’s,” he comments.

To learn more, contact Todd at wtodd3@uwyo.edu.

This article was originally published in the 2025 issue of Reflections, the annual research magazine published by the UW College of Agriculture, Life Sciences and Natural Resources.