University of Wyoming researchers are studying whether applying an insecticide early in the season and herbicide at the same time controls alfalfa weevils and helps prevent a field from becoming a buffet for pests and heartburn for farmers.

Some companies are offering the option to apply the two pesticides in one application for increased convenience. Herbicides to control weeds are usually applied earlier than the insecticide used for weevil control, and some producers are skeptical enough larvae have emerged to offer control, said Randa Jabbour, plant sciences associate professor at the University of Wyoming.

“Many producers are saying it’s helping but as of right now there is no data to back that up,” said plant sciences graduate student Micah McClure.

Researchers wanted to measure alfalfa weevil control, but also how the practice affects beneficial insects.

McClure, of Ronan, Mont., netted insects on research plots this spring at the James C. Hageman Sustainable Agriculture Research and Extension Center near Lingle. The first sweep was May 6, and he finished netting his final batch the week of June 22 on the 15 plots. He collected more than 68 bags to take back to the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources for counting.

The tiny alfalfa weevil (about 3/16 inches long) beetle is just as excited for the growing season to arrive as farmers; they overwinter in the crowns of alfalfa plants and debris around a field. Once temperatures rise to about 48 degrees, females chew holes in the alfalfa stems and deposit eggs as the alfalfa breaks dormancy, about April through May. Each female can lay 400 to 1,000 eggs. The larvae hatch and the feasting – and damage – begins.

Producers who determine the number of weevils are close to an economic threshold like to spray at least one week before they cut the alfalfa, but that decision can be derailed by factors outside their control – like weather.

“There is this really narrow window of time when these growers are trying to make these decisions,” Jabbour said. Spraying earlier could solve the timing problem.

Research by Oklahoma State University in the 1990s showed that six larvae per stem on 15-inch high alfalfa can cause a .5-ton per acre loss in the first cutting and .4 in the second cutting. The study indicated eight larvae per 15-inch stem cause a .67-ton per acre loss in the first cutting and .55 in the second. The information is in Alfalfa Weevil Biology and Management, B-983, available at bit.ly/alfalfa-weevils.

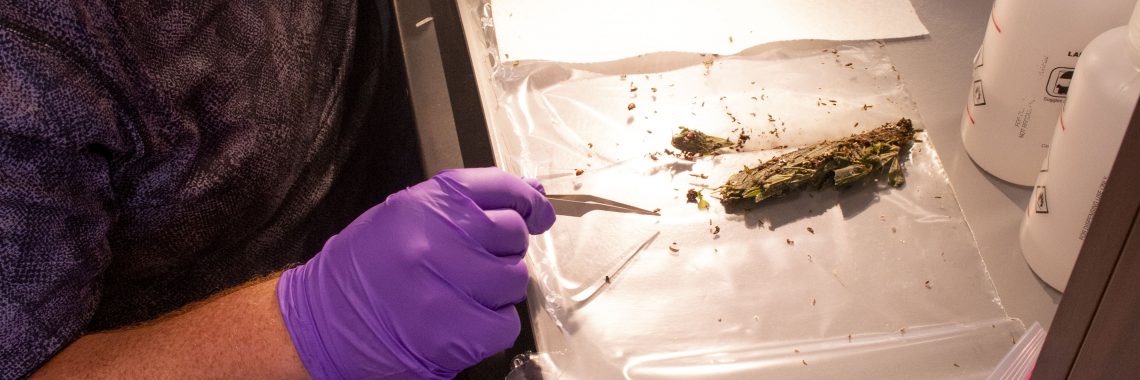

COVID-19 has slowed UW research efforts but peek in a fourth-floor laboratory in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources and you’ll see a masked McClure meticulously taking one insect at a time from a plastic bag and putting it under a microscope to determine the species and add to the running total of insects.

McClure is counting alfalfa weevil larvae and adults, clover root curculios, bees, ladybugs, damsel bugs, spider, grasshoppers, wasps, aphids and lygus bugs. Insects in Wyoming Alfalfa, a guide to the pests and beneficial insects commonly found in Wyoming alfalfa fields, is available at https://bit.ly/wyoming-alfalfa-insects.

His sweeps May 6 netted no alfalfa weevil larvae and only two adults. By May 27, that total jumped to 348 larvae and nine adults.

Weevils are a one-generation, early spring problem, said McClure, and some producers cut hay earlier to try to control the pests, but some can survive and start damaging the second cutting. The pests can then cause further harm to production because an alfalfa plant is putting all its energy into the secondary growth.

The UW effort is part of a larger grant from the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture Alfalfa Seed and Alfalfa Forage System Program and study led by Utah State University, said Jabbour. Chemists there want to determine how much and how long a pesticide stays on leaves during an application and how long it stays toxic. Jabbour said entomologists there are measuring different levels of toxicity and if the insecticide will still kill an insect over time.

UW will collect and send leaf samples to Utah State next year. Jabbour has an hypothesis that spraying earlier in cooler weather will increase an insecticide’s effectiveness.

“We think when you spray earlier (and it’s cooler), it stays around longer to be able to kill the insect than later in the season (when warmer),” she said.

More efficient spraying could also lessen weevil resistance to an insecticide. Jabbour said in the western United States there is more documentation of alfalfa weevils being resistant to some of these pesticides.

“We have not measured that in Wyoming, so we don’t know we have this resistance here, but we probably do, and it’s probably worse in certain places,” she said. “It’s a hunch.”

McClure may be able to give preliminary data on this research this fall. Jabbour said the hope is to give producers good information whether spraying early is effective, and if so, farmers could optimize when they use the product to reduce the rate of developing resistance in the insects.