When Sawyer Zook joined the University of Wyoming’s organizational leadership program in 2022, he was already a working professional well versed in plumbing, welding, and water resource management.

Despite his qualifications and work experience, Zook wasn’t ready to settle into a lifelong career just yet. He had too many unanswered questions about the world around him.

Ultimately, Zook’s quest for knowledge led him to a plant sciences lab at UW. There, his background in the trades helped him excel as an undergraduate researcher.

From plumbing to plants

Zook attended Montana State University Northern on a football scholarship while working full time, graduating with a plumbing degree and a welding certification.

Working night shifts at a water treatment plant in Montana, he was intrigued by the water use patterns he observed during the growing season. Curiosity piqued, Zook began researching irrigation systems in his free time, building on his knowledge of plumbing and pipe design. He remembers thinking, “I’ve got water, so the next step is plants.”

When Zook returned to school to pursue a bachelor’s degree in organizational leadership, he was excited to discover that UW’s Department of Plant Sciences offered a horticulture minor. He soon found that the minor offered ample opportunities to explore drought-resistant plants and agricultural systems in harsh environments.

While UW’s organizational leadership program can be completed fully online, Zook wanted to take advantage of as much in-person instruction and research experience as he could. He chose to move to Laramie, pursuing as many on-campus opportunities as he could squeeze into his schedule.

Studying drought response

Zook’s first horticultural experiment in Laramie began not in the lab, but at home.

During a summer internship in North Dakota with Pivot Bio, he’d become interested in how small grains like durum wheat were affected by drought conditions. After doing some research, Zook discovered buckwheat, a “pseudo grain” known to thrive in harsh, dry, high-elevation environments.

In other areas of the world, buckwheat is commonly used to manufacture products like pasta, flour, and soap. As an added benefit, the plant also attracts pollinators and is often grown in pollinator gardens.

For Zook, the logical next step was to order and plant buckwheat seeds from around the world, monitoring their growth over time. He mentioned the project to Randa Jabbour, an associate professor of agroecology and the instructor of Zook’s organic food production class.

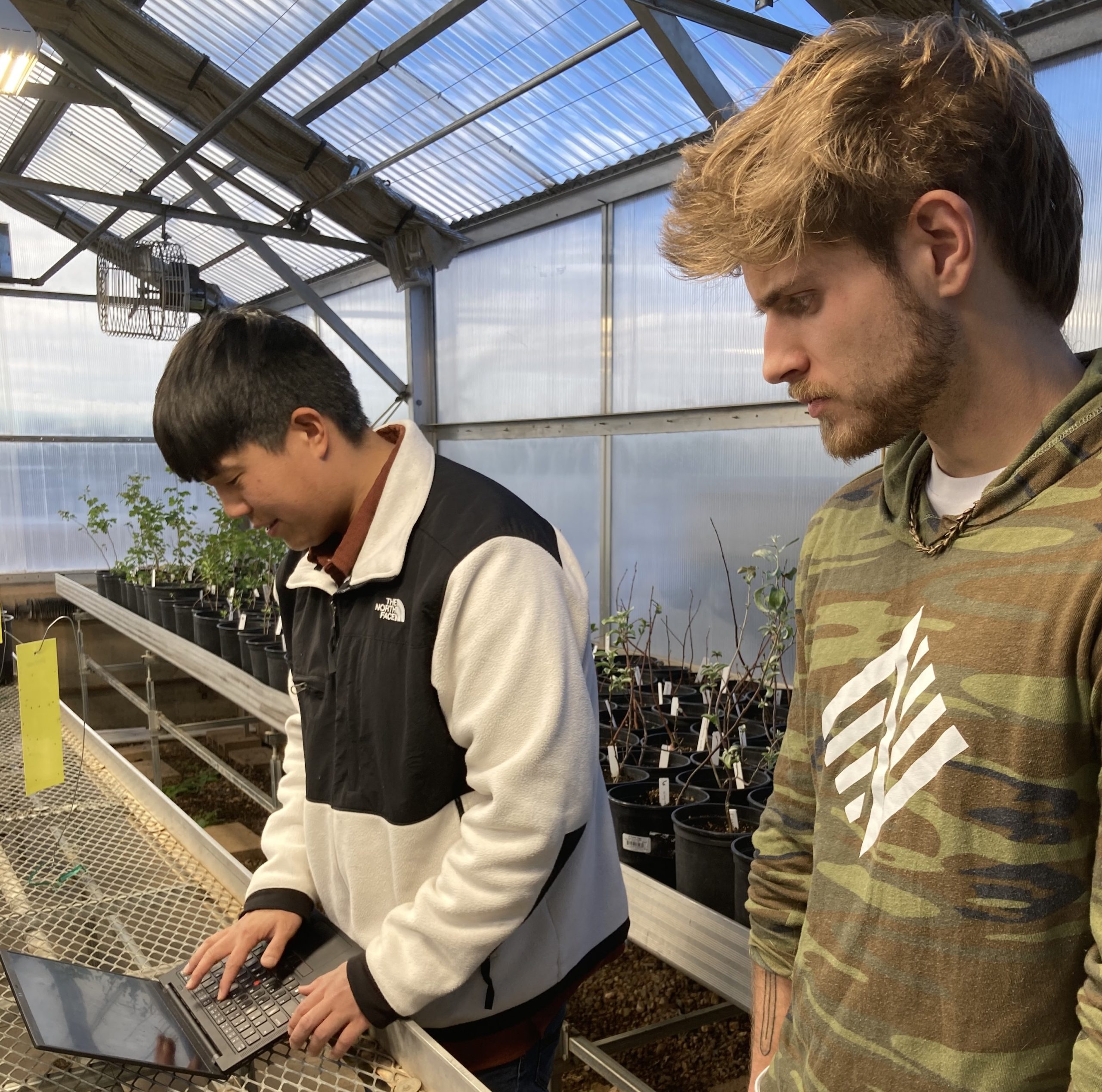

Jabbour recognized Zook’s aptitude for scientific inquiry. She suggested that he consider a research apprenticeship class and also introduced him to JJ Chen, an assistant professor of plant sciences who studies controlled environment agriculture (CEA) and drought-resistant plants, among other topics.

“I just so admire Sawyer’s tenacity not just in being a persistent person, but in really wanting to know the answers to these questions,” Jabbour comments. “One skill scientists have is being able to ask good questions, but it’s a different skill to then have the diligence to actually go after answering those questions.”

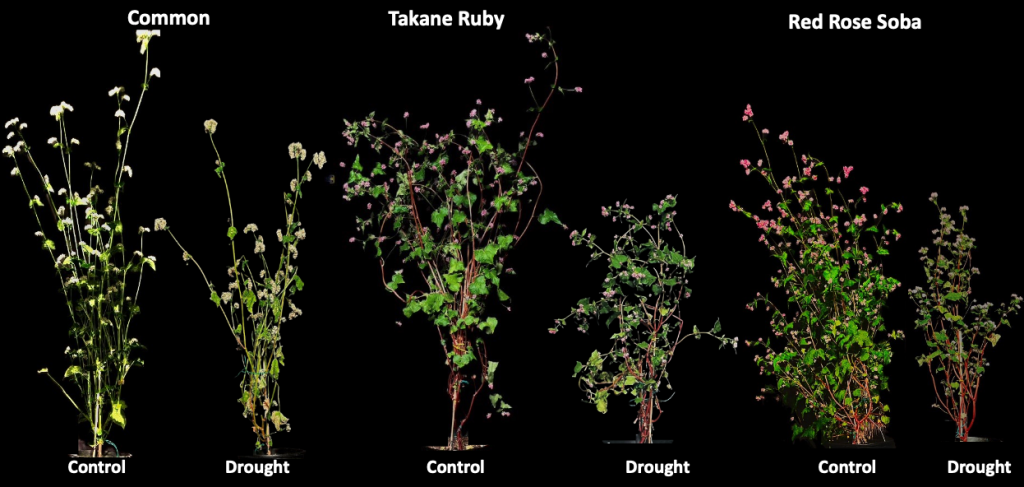

Under Chen and Jabbour’s mentorship, Zook transferred his buckwheat experiment to a greenhouse at the Laramie Research and Extension Center. In this controlled setting, Zook tested the drought response of three buckwheat varieties, including the variety most commonly grown in the U.S.

Of the three varieties Zook tested, he found that ‘Takane Ruby’, a buckwheat variety that originated in the Himalayas, was most adaptable to drought. It didn’t look that way at first—initially, the plants began to wilt in response to water stress. But they managed to survive, ultimately demonstrating the most efficient drought response.

“[‘Takane Ruby’] was able to come back and adjust to the conditions,” Zook explains. “This is classified as a drought avoidance response—it avoided the effects of drought through slowing down its growth as opposed to the common variety, which was just fighting it by bringing up minerals such as sulfur.”

At the time, Zook was one of only a few researchers in the U.S. studying drought tolerance in buckwheat. In recognition of his outstanding efforts, he earned first place in the American Society for Horticultural Science’s 2024 undergraduate poster competition.

The awards ceremony took place in Hawaii. Zook admits, with a grin, that he was just as excited to explore the local plant life as he was to attend the conference and accept his award.

Growing plants in outer space

In addition to completing a horticulture minor, Zook served as an undergraduate research assistant in Chen’s lab. In 2024, he was accepted into a Wyoming NASA EPSCoR (Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research) fellowship.

As a NASA fellow, Zook worked with Chen on a controlled environment agriculture project aimed at more efficiently growing plants on the lunar surface.

The project aligned well with Zook’s interest in drought resistance—after all, outer space isn’t the most hospitable growing environment. Currently, that means astronauts have to tote soil from Earth into space with them in order to grow fresh veggies.

But, if scientists could find a way to improve the nutrient content of lunar soil, perhaps astronauts could grow fresh produce without transporting dirt from their home planet. “We realize that the lunar soil might be really harsh for most of our plants to grow,” Chen says. “Instead of just bringing tons of organic matter from earth, how can we introduce something to enhance the organic matter [of lunar soil]?”

It turns out that that soil-enhancing ingredient might be a strain of algae developed by UW Professor John Oakey. Through a collaboration with Oakey’s lab, Chen’s team began testing whether adding this algae to low- and no-nutrient soil could improve nutrient retention and plant growth.

As part of the project, Zook helped grow, water, and monitor hundreds of lettuce plants. The plants were seeded in sand to mimic nutrient-deficient lunar soil with zero organic matter. Some of the lettuce plants received treatments of algae, while others received high, medium, and low levels of standard fertilizer.

Especially when it came to working on CEA systems, Zook’s background in the trades was an asset. While he might not have worked with thermal couplers in a greenhouse environment, he was no stranger to their application in a boiler system. “It’s interesting to draw those correlations and make those connections,” he says.

Zook graduated from UW in December 2024 and currently serves as a junior agronomist at Agrocological Solutions. Reflecting on his time at UW, he notes that “between Randa and JJ and Dr. [Liz] Moore, it’s been a great staff supporting my ideas, ventures, aspirations. I’m very grateful.”

To learn more about undergraduate research in the UW Department of Plant Sciences, contact Jabbour at rjabbour@uwyo.edu.