You’ve probably heard of—and perhaps even tried—more than a few questionable mosquito repellents.

Maybe you’ve rolled your eyes at home remedies but secretly wondered, do mouthwash, dryer sheets, and garlic really work? Or perhaps you’re considering ditching oily DEET spray in favor of a high-tech ultrasonic device or bug zapper.

But the question remains: Which methods are truly effective and which are supported only by flimsy marketing claims (or wishful thinking)?

The following gadgets are not recommended by experts and are unlikely to provide satisfactory protection against mosquitoes.

1. Ultrasonic repellents

These handheld electronic devices supposedly deter mosquitoes using high-frequency sounds, eliminating the need for chemical sprays. Some manufacturers claim that their gadgets mimic the wing beat frequency of male mosquitoes, driving away females that have already mated, while others claim the sound mimics predacious dragonflies.

But that’s not what the science says. Rutgers University reports that studies have repeatedly shown sonic repellents to be ineffective.

“I get a lot of questions about things like ultrasonic repellents,” says Scott Schell, UW Extension entomologist. “Many times these products are based on a grain of truth. Moths can hear bat calls and will take evasive action in flight when they hear bats doing echolocation. But mosquitoes don’t have that ability to hear. The idea that this sonic device is mimicking bats (or the wing frequency of dragonflies)—well, that’s not the case.”

The American Mosquito Society concludes that while marketing campaigns appealing to the public’s mistrust of chemical control have proved effective, sonic devices have no repellency value.

2. Bug zappers

An electrocution device with a demonstrated ability to attract and kill thousands of insects in a 24-hour period? Surely this is the way to go.

But these devices may not be such a great solution after all. Studies have shown that while bug zappers do kill some mosquitoes, most insects wiped out by these devices aren’t pests. Scientists at the University of Notre Dame found no significant difference in the number of mosquitoes present in yards with bug zappers compared to those without.

Even worse, many of the non-pest insects killed by bug zappers prey on pest species. These beneficial insects also serve as important food sources for other organisms, such as songbirds.

3. Dryer sheets, mouthwash, and more

Forget all those fancy, highfalutin devices—what about going back to the basics? Some people swear by minty mouthwash, while others tout scented dryer sheets.

As with other mythical cures, these questionable tactics harbor a grain of truth. “Listerine would have some short-term repellency because menthol is one of many volatile chemicals that provide a powerful smell that masks your presence,” says Schell. “But most of these products are short lived. They don’t last long enough to provide you protection through an evening in your yard.”

Perfumed dryer sheets share a similar story. Their powerful fragrance may act as a short-term repellent, but doesn’t last for a meaningful period of time.

Scented dryer sheets perfumed with linalool and/or citronella certainly made the old hat smell better and with one sheet over each ear and one in the back, they did protect the wearer’s head from mosquitoes while the fragrance was potent. However, the hat-deployed dryer sheets tested did not protect the arms or legs from the mosquitoes that inhabit the Laramie River Valley and were annoying when they started flapping in the breeze.

-Scott Schell, UW Extension Entomologist

4. Carbon dioxide traps

Mosquitoes are drawn to the carbon dioxide you exhale. When they come closer to investigate, they detect their next blood meal. So, what about using a trap that emits carbon dioxide?

A good idea in theory, but so far, these traps aren’t a reliable source of protection. While they do capture mosquitoes, studies indicate they don’t reduce the rates at which humans are bitten. Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison also note that the traps they tested broke easily and some manufacturers made claims that couldn’t be verified.

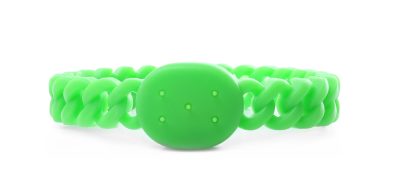

5. Wristbands

Bracelets treated with insect repellent sound like a convenient option, especially when the alternative is spraying oily products onto your skin. But it turns out these devices aren’t very effective either.

Part of the problem is that wristbands provide only localized protection. While a bracelet may repel mosquitoes near your wrist or lower arm, it doesn’t offer full-body protection. A wristband containing DEET repellent, paired with other deterrents (like protective clothing and topical repellents) may provide some benefit, but is not recommended as a go-to option.

None of the three wristband products tested in a 2017 study published in the Journal of Insect Science resulted in a significant reduction of mosquito attraction. The researchers hypothesized that the concentrations emitted by those products were too low to provide measurable protection.

6. Citronella candles and natural repellents

Consumer Reports advises against relying on natural repellents (such as clove, lemongrass, and rosemary oils) and citronella candles. Their testers found that natural repellents did not last as long as other products.

They also point out that natural repellents are not subject to the same regulations and rigorous testing the Environmental Protection Agency requires for other products. Since the chemicals contained in natural repellents are deemed harmless, companies are not obligated to provide evidence of their efficacy.

Citronella candles were also deemed ineffective, a finding corroborated in the 2017 study published in the Journal of Insect Science. While citronella oil has mosquito-repelling properties, citronella candles do not tend to provide adequate protection.

“A citronella candle in calm conditions where you’re getting a lot of fragrance around you could probably provide some protection,” says Schell. “But they’re not considered highly effective.”

7. Fuel-powered mosquito repellent devices

These devices, touted for their ability to create mosquito-repelling zones, use a butane fuel cartridge to vaporize pyrethroid insecticides, such as allethrin. “It’s based on the idea that you’re surrounded by a cloud of allethrin vapors—and it works,” says Schell.

However, these gadgets aren’t a great choice at high elevation or in windy conditions (both of which tend to be common in Wyoming). “At our altitude [7,220 feet] in Laramie, oxygen content is not very high. If you’re at low elevation (specifically, less than 4,000 feet according to a leading manufacturer) and it’s calm, these products provide some protection,” Schell explains.

Similar products that use electrical power (instead of fuel) to create a repellent vapor cloud are better suited to high-altitude use.

So, what does work?

Currently, DEET and picaridin are the two active ingredients most effective at repelling mosquitoes.

Despite common misconceptions, DEET products are used extensively with little risk to human health when applied appropriately and to label instructions.

Note that a higher concentration of DEET in a product means that the product will remain effective for a longer period of time. A higher concentration does not mean that the product is better at repelling mosquitoes.

If you’re going on an extended adventure in area with a lot of biting mosquitoes, Schell recommends purchasing an encapsulated DEET product. These repellents release DEET slowly over time rather than spiking and then dropping. These products also tend to have a lower DEET concentration, which can be more comfortable on the skin in hot, humid environments.

If you’re only going to be outside for four to six hours or so, repellent sprays containing 20 to 30 percent picaridin are another good option, says Schell. Picaridin is a synthetic chemical that mimics an insect-repellent compound present in some pepper plants.

Studies have shown that picaridin-based repellents provide similar protection to DEET-based repellents. Consumer Reports recommends picaridin pumps or sprays over lotions or wipes.

Your product selection will likely vary depending on activity type, duration, and location. “Try to consider products that match your needs,” Schell advises. “If you are only going to be out for a short time, maybe use some of those more pleasant, shorter-acting products. If you’re going on a long expedition in the Canadian bush, you’ll want the best, or it’s going to be a miserable trip.”

Finally, don’t forget to take susceptibility into account. Mosquitoes find some unfortunate humans more attractive than others. “You can have two people sitting out on a deck, one with no repellent on, and the other getting a bunch of bites even with repellent,” Schell notes. “Keep in mind there’s a lot of susceptibility differences.”

For more advice on mosquito management and other insect issues, contact Schell at sschell@uwyo.edu.