Graduate student Jack Alford studies wildlife populations in the arid, high-elevation landscapes of southern Wyoming. But his roots trace back to the humid, hurricane-prone Florida coast.

When Hurricane Milton swept across his home state in October 2024, Alford was thousands of miles away. But he quickly became involved in relief efforts from afar, working with a team of UW faculty and students to provide disaster-mapping services.

Joining the disaster-mapping team

Under the guidance of Ramesh Sivanpillai, an instructional professor in the School of Computing and Wyoming Geographic Information Science Center (WyGISC), Alford and 31 fellow volunteers combed through thousands of images to identify damaged homes and structures in five Florida communities.

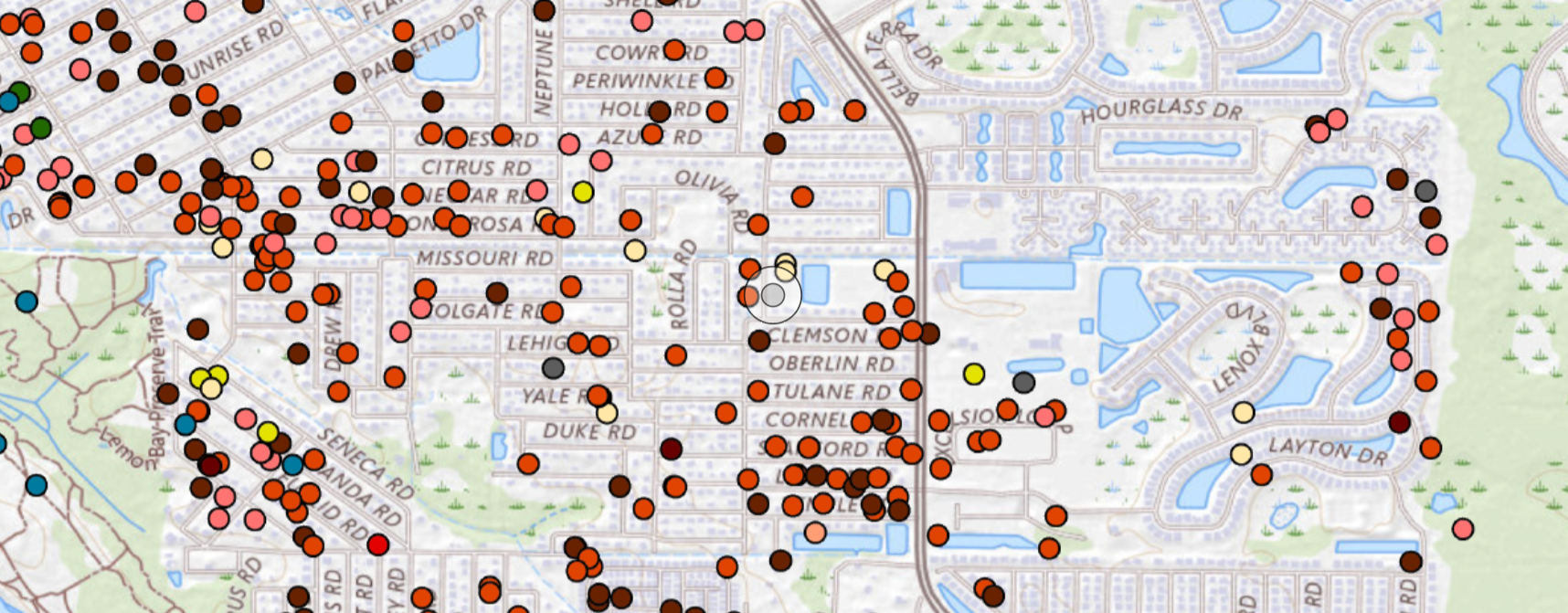

In total, they recorded more than 3,400 points of damage using images provided by the U.S. Geological Survey. The disaster maps they generated, which displayed the locations and types of damage, were used by federal and state management agencies during field visits.

“We were helping out people on the ground by going through these images and finding sources of damage so FEMA and other organizations could allocate their assets to the best of their ability to the areas where they’re needed most,” Alford explains.

Sivanpillai regularly leads disaster-mapping efforts coordinated by the International Charter Space and Major Disasters. When the organization contacted him in the wake of Hurricane Milton, Sivanpillai quickly mobilized and trained a group of volunteers.

At the time, Alford was enrolled in Sivanpillai’s introductory remote sensing class. As a grad student in the Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, he planned to incorporate satellite images and remote sensing tools into his research, which examines how sage-grouse may interact with future wind energy infrastructure.

Then, “Professor Sivanpillai reached out about an opportunity to get involved with this storm damage classification,” Alford recalls. “It was a strong motivator because I’m a Florida native and in 2018 I went through the eye of Hurricane Michael.”

Alford and his family experienced the Category-5 hurricane and its aftermath firsthand. He knew what it was like to weather both a devastating storm and the recovery process that followed.

Interpreting images

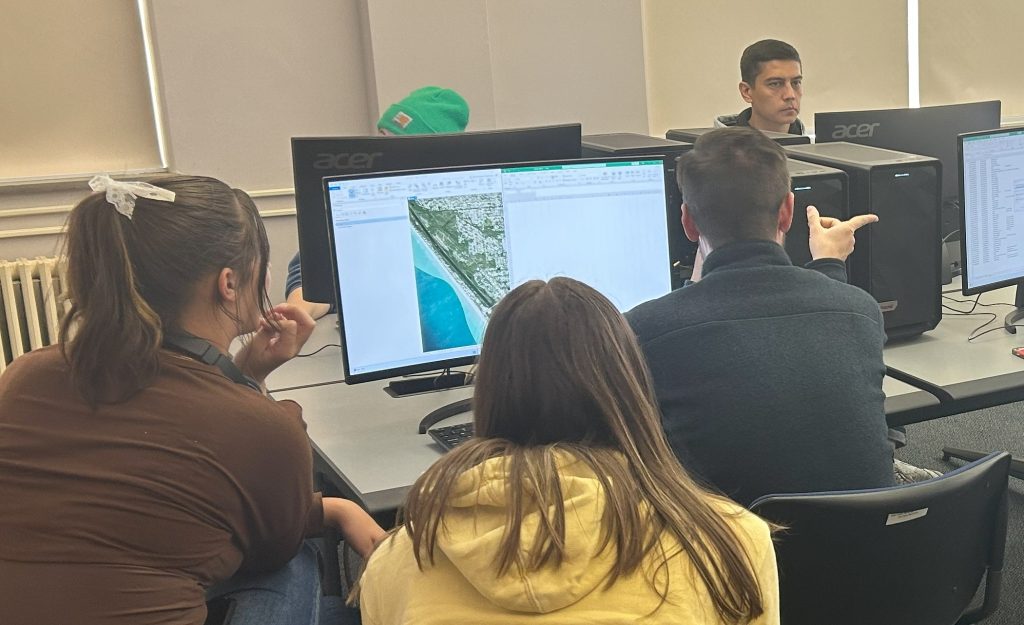

In fall 2024, Sivanpillai led five disaster-mapping sessions to help identify structures damaged by Hurricane Milton. Student volunteers contributed a total of more than 250 hours to the effort.

During each session, volunteers viewed designated areas in ArcGIS, a geospatial data analysis software, and compared pre-Milton satellite imagery with post-Milton images taken via airplane. They painstakingly zoomed in and out to inspect potential damage to homes, pools, docks, and even boats.

When volunteers spotted a damaged or displaced structure, they recorded the site’s geographic coordinates and assigned it to one of 16 damage categories. Damaged or missing roofs were the most commonly observed types of damage, but Sivanpillai’s team also noted the locations of structures and debris swept up by the hurricane and deposited in roadways and backyards.

The task wasn’t always straightforward. A boat stranded in a backyard, for example, may have initially been placed there by a resident preparing for the storm, not hurled through the fence by the hurricane. If they had any doubts, volunteers added notes in the comments section.

In cases where they noticed flooding or leaks, volunteers also noted the potential for internal damage. In a humid environment like the Florida coast, it’s crucial to address these issues as quickly as possible to avoid secondary damage like mold, Alford explains.

Since the post-hurricane images were taken up to a week after the storm, volunteers had to keep an eye out for initial cleanup efforts that might’ve masked the full extent of the storm’s destruction. They also had to watch out for issues that could have been caused by a previous storm; in some cases, for instance, a house’s roof might have been covered by a tarp before Milton even hit the area.

The value of volunteering

Since Alford had experienced hurricane wreckage firsthand, he was well equipped to spot damage that others might overlook. In fact, he even helped train fellow volunteers.

“The recovery from these storms really does take a village,” he comments. “When you go through these images, it may be every house in a neighborhood that has damage…That really adds up and puts it into perspective just how life-changing of an event these huge storms can be.”

Although he was busy with classes and preparation for his second season of field research, Alford prioritized volunteering, attending four of the five disaster-mapping sessions Sivanpillai organized.

“As someone who went through a situation like this, knowing that it was possible someone did this for my situation…I felt compelled to come in and help as much as I could,” Alford explains. He encourages other members of the UW community to volunteer when the opportunity arises.

To view the disaster maps generated by UW volunteers, visit https://bit.ly/milton-maps-uw.