What does a retirement community of plants look like?

In a groundbreaking international study that spans 90 sites—including one near Lingle, Wyoming—and 32 countries, scientists are searching for answers.

More specifically, they’re examining how the species composition of grassland plant communities changes over time when former agricultural fields are abandoned (no longer fertilized and tilled).

This grassroots project is known as the Disturbance and Resources Across Global Grasslands, DRAGNet for short.

Local data collection will offer clues as to how changing land use may affect forage quality and the prevalence of native Wyoming species versus invasive annual grasses, says Lauren Shoemaker, UW assistant professor of botany and a DRAGNet project lead.

“Many people in the state are invested in maintaining biodiversity and biomass production of grasslands for range systems,” she notes. “If we’re switching how a land is being used and the human impacts on it, can we make general predictions of what will happen, both in terms of the recovery of species diversity and the production of quality forage?”

While the study relies on a relatively simple experimental design, DRAGNet is unusual not only in its geographic reach, but also in its approach, which standardizes treatments and data collection procedures across all sites. This allows researchers to detect global patterns as well as local trends—without the frustration of trying to compare results from studies following similar, but slightly different, research protocols.

Scientists at each site have committed to three years of disturbance treatments and a minimum of five years of monitoring.

In 2022, Shoemaker and her team completed “year zero” at the James C. Hageman Sustainable Agriculture Research and Extension Center. Pre-treatment results revealed substantial hidden diversity in the seedbank; approximately 67 percent of the species waiting patiently underground to germinate were not present aboveground. Surprisingly, the dominant species aboveground (needle and thread grass) is rare in the seedbank.

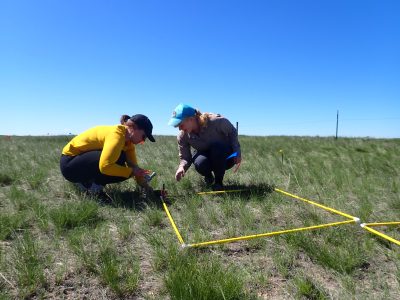

For the next three years, Shoemaker’s team will till, rake, and add nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) to the test plots, returning twice during the growing season to painstakingly identify plants by species in 1-meter by 1-meter squares, estimate percent coverage, and collect biomass for lab analysis.

“Our plan is to collect data as long as possible because a lot of these changes are slow to emerge,” she explains. “Oftentimes it’s 10 to 20 years before you really see where the community settles.”

In addition to recording DRAGNet-specific measurements, Shoemaker is also collecting seed dispersal data and working with UW colleague Linda van Diepen to analyze changes in microbial communities.

It’s one of her favorite aspects of the project: only one-quarter of the area of each research plot is designated for specific tests. The rest is available for other projects dreamed up by students and faculty members.

“It’s really exciting because it means we can add new experiments in areas that have already received treatments and even propose new experiments across multiple sites,” she says.

To learn more, visit nutnet.org/dragnet or contact Shoemaker at lshoema1@uwyo.edu.

This article was originally published in Reflections 2023 magazine, the College of Agriculture, Life Sciences, and Natural Resources annual research magazine.