For ranchers in Wyoming and throughout the West, non-native weeds often are a frustrating and severe threat to rangeland health and livestock production. When non-native weed species invade, ranchers can be hit with a double-whammy—weeds that are both unpalatable or toxic to horses and cattle and likely to reduce the abundance of high-quality forage.

Russian knapweed (Figure 1) is a widespread, invasive weed that has been in Wyoming since the late 1800s, when it probably was introduced as a contaminant of alfalfa seed. Its native range consists of central Asia, from Turkey east to China, and Iran north to southern Russia. Cattle tend not to eat Russian knapweed, and it is poisonous to horses, sometimes fatally. According to estimates from the Wyoming Weed and Pest Council, 21 of 23 counties have Russian knapweed, encompassing as much as 100,000 acres.

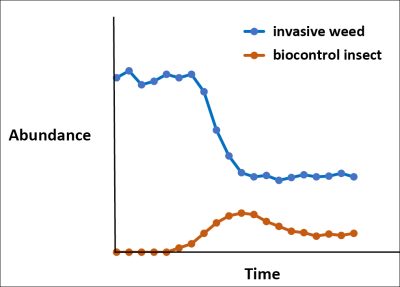

In the 1990s, the Wyoming Weed and Pest Council started to fund a “biological control” or “biocontrol” program for Russian knapweed. Biocontrol is the importation of insect herbivores from the weed’s native range. Ideally, the weed biocontrol process should resemble the graph in Figure 2. Initially, the weed occurs at damaging levels, but after the biocontrol insect is introduced, weed abundance declines dramatically. After introduction, the insect population grows but then declines as weed abundance decreases, although the decline in the insect population occurs with what is called a “lag,” i.e., it declines after the weed does. In the long term, however, the insect continues to reproduce, damage the weed and spread on its own, so suppression of the weed occurs indefinitely over large areas.

Overseas research for the Russian knapweed biocontrol program was conducted by the non-profit Center for Agriculture and Bioscience International. Insect surveys by CABI in central Asia identified a half-dozen species of insects that feed on Russian knapweed, including the knapweed midge, Jaapiella ivannikovi (Figure 3). About the size of a mosquito, knapweed midges lay their eggs on Russian knapweed shoot tips, causing a “gall.” Each gall is a spherical bunch of distorted plant tissue, within which the midge larvae shelter, feed and grow (Figure 4). Galls negatively affect the weed by diverting nutrients and energy needed for plant growth and reproduction.

According to CABI research, the knapweed midge is specific to Russian knapweed and one other Asian plant species, garden cornflower. Garden cornflower is an ornamental species that is grown in the United States, but like Russian knapweed, it is considered an invasive weed. Based on the data collected by CABI, the U.S. Department of Agriculture approved importation of the knapweed midge. Midges were collected in Uzbekistan, reared through multiple generations in a quarantine facility at Montana State University, then released for the first time in Wyoming at a site near Riverton in May 2009 (Figure 5).

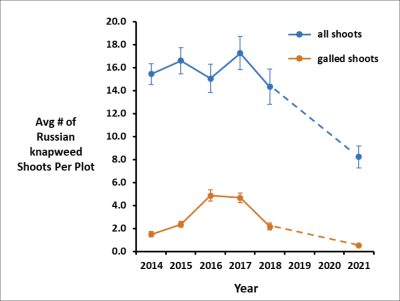

Since that initial release, and with funding from the Wyoming Weed and Pest Council and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, I have continued to release knapweed midges at new sites across Wyoming. I also have been researching the population dynamics of Russian knapweed and the midge at the first site near Riverton. From 2014 to 2018, and again in 2021, I surveyed populations in 60 research plots by counting knapweed shoots in the spring, then counting galls and galled shoots every three weeks from June through August.

My research shows that the number of Russian knapweed shoots has declined since 2017 (Figure 6). Although the graph resembles the idealized process of weed biocontrol depicted in Figure 2, a notable difference is that the decline in midge abundance seems to have occurred at the same time as the decline in knapweed abundance, rather than with the expected lag.

Data for 2019 and 2020 may have shed more light on the relative timing of the declines, but the pattern I observed still is broadly consistent with effective biological control. Surveys are ongoing in 2022 and beyond. It will be interesting to see if the pattern of lower Russian knapweed abundance persists.

There is good reason, however, to be cautious about interpreting the decline in Russian knapweed abundance in this way. The data are from a single site and did not include a control group of survey plots where the knapweed midge was absent. It therefore is possible that some factor other than the midge may explain the decline in knapweed abundance.

Using data from the Western Regional Climate Center, I explored the potential effects of precipitation, which can have significant effects on weed abundance. I discovered that when knapweed abundance was at its peak in summer 2017, the preceding eight months (October–May) were particularly wet. Relative to October–May precipitation from 1930–2021, precipitation prior to summer 2017 was 2.5 times greater than average. Precipitation during the October–May period prior to summer 2016, another high point in knapweed abundance, was twice as high as average.

By contrast, during the winter and spring prior to the 2021 surveys, precipitation was a bit less than average (90% of the average since 1930) and Russian knapweed shoot abundance had fallen to the lowest level that I have observed so far. In fact, across all the survey years, there was a broad correlation between knapweed abundance and October–May precipitation, with more knapweed shoots present in wetter periods. This points to the possibility that Russian knapweed may have declined, not because of the suppressive effects of the midge, but due to lower precipitation in 2021.

So, is Russian knapweed biocontrol working? Possibly, but the jury is still out. More time and more population surveys are needed. If biocontrol is working, then the abundance of both knapweed shoots and galled shoots eventually should level off, as in Figure 2. However, a rebound in knapweed density and/or a continued decline in the population of already-scarce midges would suggest otherwise.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that another insect biocontrol agent has been released in Wyoming and has established self-sustaining populations. The agent is a gall-forming wasp called Aulacidea acroptilonica (Figure 7), also from Uzbekistan. The gall wasp is beginning to appear in my research plots near Riverton, although it is still relatively rare. At other sites in Wyoming, the gall wasp has increased substantially in abundance, and early-stage surveys of this species are ongoing. The Wyoming Weed and Pest Council also is funding CABI to conduct overseas research on a new potential biological control agent for Russian knapweed—an Uzbek species of “jumping” weevil (Figure 8) that damages knapweed leaves. Clearly, there is cause for optimism. Biocontrol of Russian knapweed is proceeding well, and hopefully the impacts of one or all of these agents will one day mean that Wyoming livestock producers will have fewer problems with this troublesome, invasive weed.

By Timothy Collier, Associate Professor, Department of Ecosystem Science & Management, (307) 766-2552, tcollier@uwyo.edu.

Reprinted from Reflections 2022.