The director of the laboratory testing University of Wyoming COVID-19 samples was describing how the Wyoming State Veterinary Laboratory (WSVL) came to be testing 2,500 samples a day when he stopped mid-sentence and changed facial expressions.

“Let me just step back a minute,” said Will Laegreid, a professor in the Department of Veterinary Sciences.

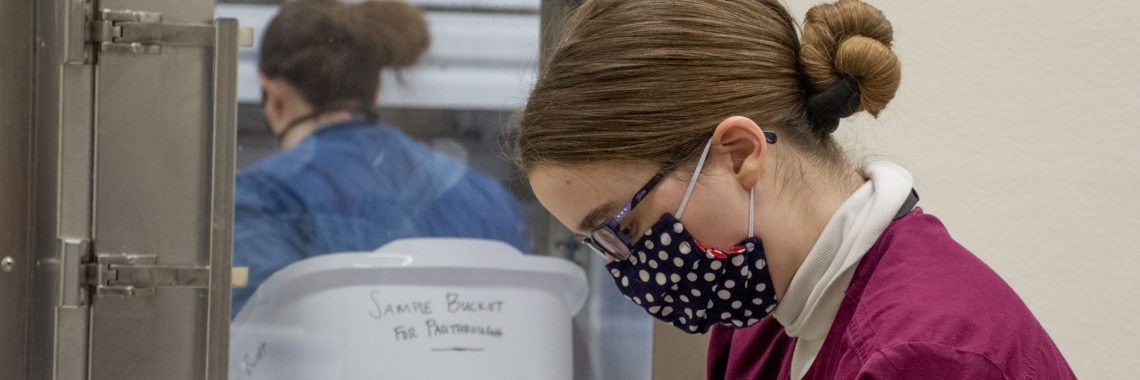

Vault Health provided diagnostic testing services to UW until the WSVL took over diagnostic testing in December, literally saving the state of Wyoming and UW millions of dollars, Laegreid estimates. Tests are conducted in the UW Biocontainment Facility.

Hundreds of UW employees are involved in the scheduling, testing and results process, from taking samples, to testing, to creating the digital communication infrastructure, to student and employee contacts and then helping quarantine those testing positive.

“It’s really striking,” said Laegreid, who specializes in the pathogenesis and control of animal diseases. “One of the greatest things about this is it’s been really great working with the people who have been involved in this overall program. And it sounds hokey, but we have some really, really excellent people on this campus, and they have really gone beyond the extra mile to get this testing program to work.”

The effort hasn’t been easy, he added, “But it’s sure been a whole lot more pleasant than it could have been. And it would have been impossible without everyone just pitching in. And that’s continued.”

UW is now testing all undergraduate students spending time on campus twice per week, while graduate students, faculty members and staff members are tested weekly. The university also offers free COVID-19 testing to the broader Albany County community. The testing program, one of the most innovative in the nation, is a key component of the university’s efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19.

“We’re extremely grateful for the work done by the WSVL team and others to make it possible for the university to conduct its own testing program,” UW President Ed Seidel said. “Their efforts, and the compliance of our students, faculty and staff, have helped us maintain a safe environment on our campus — and set the stage for returning to a more traditional semester this fall. I’m proud of the team and university for achieving this national leadership role while serving our community.”

Efforts began not long after Seidel arrived on campus July 1. Seidel had indicated in a late-July meeting a desire for intensive testing of students, staff and faculty members, with the goal of limiting the infection in the UW community.

That was important, said Laegreid, because stating the reason why then directed what testing would be done, what would be done with the data and how many people would be tested.

Laegreid said information at the time indicated about 80 percent of the infectivity could be removed from campus if everyone on campus was sampled every two to three days and those testing positive quarantined.

Nationwide data made clear universities and similar institutions were hotspots of infection for their surrounding areas.

“We really wanted to avoid UW being a source of infection for other people,” he said.

UW ditched the nasal pharyngeal swab test, the sample of choice at the time, to follow such schools as Yale and the University of Illinois that use saliva testing. Accuracy is as good or better than the nasal swab, Laegreid said.

The decision was common sense.

“(Nasal pharyngeal swabs) are pretty unpleasant,” he said. “And, if we were trying to do people twice a week, that would last about half a week, because no one’s coming back voluntarily to do that twice.”

WSVL conduced surveillance or screening testing from October to December, when the lab was Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments registered, which allowed human diagnostic testing. The lab is awaiting certification but can provide diagnostic testing while registered. Surveillance or screening tests the likelihood someone may be positive; diagnostic testing changes the management of an individual, such as warranting quarantine.

Ramping up to more than 10,000 tests a week began to strain the six diagnostic technicians who had volunteered to do the tests in addition to their day jobs. A robotic liquid handling system, delayed in getting to the laboratory, has eased the load, and another technician has been hired to operate that equipment.

High throughput testing is not usual for the WSVL. Getting 1,000 test samples from a ranch is not unusual.

“We were able to apply those skills and knowledge we already had from doing animal testing and apply to human testing,” Laegreid said. “And I think that’s why we were able to do it effectively and efficiently with a small number of people.”

Laegreid praises Dr. Brant Schumaker, a WSVL veterinary epidemiologist, for his efforts. He organized students and other volunteers for the expanded COVID hub, which involves checking in people when they arrive for vaccinations, monitoring them after they receive their shots and recording the vaccinations for the Wyoming Immunization Registry.

“(Brant) is a really good example of an infectious disease epidemiologist who’s worked on animal diseases his whole career. But, you know, people are animals, too,” Laegreid said.

“And he was able to go in and help establish the parameters for sampling our UW population to hopefully achieve an 80 percent reduction in infectivity on campus and then just on the nuts and bolts of traceback and quarantine and setting up those processes. He’s just been tireless, and he’s shifted that over now to vaccines. And honestly, the vaccine program in Albany County would not be where it is now without his efforts.”