Table of Contents

Laramie’s Rocky Mountain Herbarium is well known among the research community and botanists, but the rest of the state may not know what a resource they have tucked away in the old Aven Nelson building.

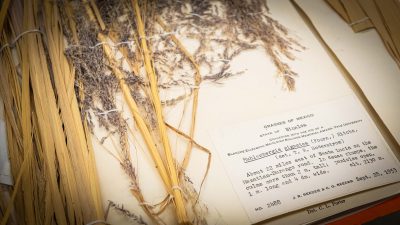

An herbarium is like a library for plants. If you’ve ever pressed a flower between the pages of a book, you’ve participated in something similar to herbarium preservation. But herbarium collectors go a step farther, preserving the plant’s leaves, stems, and other identifying features. They also record detailed information about exactly when, where, and why the plant was collected.

Day to day, botanists use the Rocky Mountain Herbarium (RMH) to identify new specimens, figure out where to look for specific species, and recognize threats to biodiversity.

The inestimable impact of historical collections

The Rocky Mountain Herbarium boasts one of the largest herbaria collections in the U.S. and in the world. It is a forerunner of specimen digitization; about 900,000 of its more than one million specimens are available online. In the U.S., only the New York Botanical Garden has more digitized specimens.

Like other educational archives, the full value of this repository of biological history is incalculable.

While he was collecting his first specimens in the 1890s, RMH founder Aven Nelson couldn’t have dreamed of how his specimens would be used today. Genetic sequencing, for example, has helped show that many invasive plants have inadvertently been bred to be more resistant to herbicides over the past decades.

“The idea is that these specimens will be used a hundred years from now, probably in ways we don’t think about at all right now,” says David Tank, current director of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium.

Devoted directors and 52 floristics students

How did a little herbarium in Laramie end up with one of the largest, most active collections in the world?

Like most extraordinary situations, individual passion and luck both played a role.

The Rocky Mountain Herbarium has had more than its fair share of passionate individuals, from founder Aven Nelson, who served as president of UW from 1917 to 1922; to W.G. Solheim, who established a mycological collection that now contains 48,000 fungal specimens; to Ron Hartman, director of the herbarium from 1977 to 2016.

During his tenure, Hartman started the floristics program with the goal of writing a flora of the Rocky Mountains. He sent graduate students into the field for full summers, collecting hundreds of samples in new habitats every week. Since that time, 52 graduate students have graduated from the UW floristics program.

“No other universities do floristics projects at the same scale,” says Ben Legler, digital curator at the RMH. “The closest is in California Botanic Garden as part of the Claremont Graduate University—but they’re surveying a few hundred square miles rather than a few thousand.”

Labels and digitization

Most herbaria began digitizing their collections in the 2000s or even the 2010s. The RMH, on the other hand, began digitizing in the 1980s and 1990s.

At first, the idea wasn’t to “digitize” at all. Hartman and longtime RMH curator Ernie Nelson just wanted to develop an efficient process to create specimen labels. Labels often include information about the specimen’s coordinates and elevation; ecological data about the locality, including habitat characteristics and associated species; details like flower color, height, or abundance; info about whether the specimen is flowering or fruiting; the specimen’s scientific name; the date collected; and who collected it. With hundreds of samples showing up each week, it was worthwhile to invest early in data entry.

Later, Legler, at the time a research assistant in the UW floristics program, was hired to collect all the files into one searchable database. Legler’s work at the RMH became the template for a collaborative online portal he helped develop for the Pacific Northwest region while working at the University of Washington. Legler’s projects ultimately sparked other efforts to pull information from multiple herbaria into regional or taxonomical online archives.

“A lot of the effort in the past has been on digitizing, just taking physical data and putting it online—but I’m interested in synthesizing that data, not just having the raw data,” Legler says. Going forward, he wants to create online field guides with checklists of what species occur in an area. That would allow even casual users to have a better understanding of their natural environment and the plant species around them.

Outgrowing the third floor

At the moment, many of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium’s priceless specimens are stacked on top of cabinets in cardboard boxes. “One leaky roof and we’d lose them,” Tank comments wryly.

For over 20 years, the collection has been crammed into its space on the third floor of the Aven Nelson building. In 2023, Tank secured a National Science Foundation grant to renovate and expand the herbarium into the second floor of the building. By the end of the three-year project, he plans to properly house all one million specimens in museum cabinets.

As part of a larger grant to digitize specimens in herbaria across the U.S., Tank’s team will also continue to digitize data and images. The RMH website currently provides data on about 900,000 specimens; 400,000 include images as well.

But even as employees race to digitize old samples, the RMH continues to amass new specimens. Some students are now sent out to re-survey localities where specimens were first collected 40 or more years ago. This allows scientists to identify what new plants are there and what plants aren’t there anymore, both of which can inform biodiversity management.

Protector of plants (and of botanists)

Herbaria can help botanists come up with strategies to mitigate conservation threats. “Herbaria are sentinels against the loss of biodiversity, and they’re the first place we see invasive species,” says Brent Ewers, head of UW’s botany department.

Through herbarium records, conservationists can understand how sensitive species might react to climate change or how invasive species might spread. They can even advocate to take species on or off endangered species lists.

Despite the value of herbaria collections, Ewers cautions, “There’s a worldwide deficit in botanical expertise, and it keeps declining.”

The Rocky Mountain Herbarium is one of the generators of the botanical workforce across the U.S. Crista O’Conner, who is an alumna of the UW floristics program and now works for the Boise National Forest Service, agrees. “As a botanist, it’s really difficult to find a program that emphasizes taxonomy and biogeography the way the RMH does. Working alongside some really incredible taxonomy giants during that experience was life changing.”

Public outreach and access

For decades, the Rocky Mountain Herbarium has not just amassed knowledge, but also prioritized sharing that knowledge. “Our goal is to take the data that’s been locked in these cabinets for hundreds of years and put it out into the world,” says Tank.

Users of the RMH seem to feel this goal has been accomplished. Kurt Flaig, a botanist with Western Ecosystems Technology, highlights the unique accessibility of the RMH and generosity of its curators. Other botanists, too, mention the curators’ willingness to work with them to identify tricky species or lend them specimens or equipment. “Having access to the RMH and all their specimens is just priceless,” says Greg Pappas, a botanist with the Medicine Bow-Routt National Forests.

Since taking the director position in 2021, Tank has focused on public outreach. “The research community knows about us, even internationally, but we’re still working on making this info more accessible in general,” he says.

Recent outreach efforts have included development of educational resources. For example, the herbarium worked with a graduate student in the College of Education to develop a cheatgrass module, which includes maps of where cheatgrass was detected over several years. This module is mailed to elementary-school students across the state to help them learn about how invasive species spread.

Herbarium staff have attended STEM carnivals and taken part in Saddle Up, a program for incoming UW freshmen. The RMH has also hosted plant walks, field trips, and curatorial nights. Going forward, Tank is also interested in building more art-science interfaces to bring out the aesthetics and beauty of the specimens, as well as building curriculum for public education.

Tank encourages anyone who’s interested to come by and mount a few specimens, which involves carefully gluing the pressed plants to archival paper. “It’s fun, it’s rewarding, and it needs to get done!” he says.

The Rocky Mountain Herbarium is a hub for the botanical community on campus and even across the West. These communities work to safeguard endangered species, botanical knowledge, and the legacy of one of the largest collections of botanical specimens in the U.S. “I’d just like to give a plug about herbaria for scientists, land managers, and anyone interested in plants,” says Pappas. “I’d encourage everyone to use and support our local RMH. It’s a special place with so much to offer.”

To get involved or donate to the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, reach out to Tank at dtank@uwyo.edu or explore their website.