As a NASA researcher, University of Wyoming student Drea Hineman studies sustainable food production in reduced-gravity environments—in other words, space farming.

A UW senior from Gillette, Hineman is majoring in plant production and protection with a concentration in horticulture. In addition to juggling work, classes, and homework, she spends hours every week monitoring lettuce plants in the Laramie Research and Extension Center greenhouse as part of a self-guided, NASA-supported research project.

Discovering controlled environment agriculture

Growing up, Hineman didn’t dream of a career in space farming. A hockey star in high school, she excelled on the ice but didn’t bring the same enthusiasm to her schoolwork. In class, her ADHD often left her squirming and disengaged. She enjoyed gardening with her grandfather, but wasn’t interested in traditional production agriculture. She hadn’t found her passion yet.

That changed when she discovered controlled environment agriculture. The idea of growing plants in a greenhouse environment with high-precision equipment immediately appealed to Hineman. She was especially interested in cannabis production, a growing field that she determined would offer an economically viable opportunity to open her own horticulture business.

As an undergrad at UW, Hineman enthusiastically dove into classes like greenhouse management and environmental instrumentation.

That’s how she met JJ Chen, an assistant professor in the plant sciences department who specializes in controlled environment agriculture. Soon, Hineman had accepted a research apprentice position in Chen’s lab; later, he became her mentor in the Wyoming NASA Space Grant Consortium fellowship program.

“She was working on a specialty crop project [in my lab], then she started to cultivate her own ideas about salinity [that were] relevant to the fellowship,” Chen recalls. “This is her own idea, her own research.”

The Wyoming NASA Space Grant Consortium sponsors education and research programs in support of NASA missions. Its undergraduate fellowship program is very competitive, Chen notes. Of the 29 undergraduates who applied for the 2025 fellowship, Hineman’s application was ranked first.

“I never thought that I’d be capable of this,” Hineman says. “But once I found out what I was really interested in, that’s when I realized my drive to want to learn about things.”

Studying salinity stress in “space lettuce”

Hineman’s fellowship project addresses a key problem astronauts face when cultivating lettuce plants in space: salt accumulation in the soil.

That’s because reduced gravity also means reduced drainage. Aboard the International Space Station, water doesn’t drain down into the soil like it does on Earth—and neither do the salts dissolved in that water. Instead of exiting the “growing pod” where astronauts cultivate lettuce plants, mineral salts accumulate in the soil and stress the plants.

Starting in July 2025, Hineman designed and executed a series of experiments examining salt tolerance in lettuce exposed to environmental stressors present in reduced-gravity environments. To mimic water movement under reduced-gravity conditions, she used an automatic sensor-based irrigation system at the Laramie Research and Extension Center greenhouse.

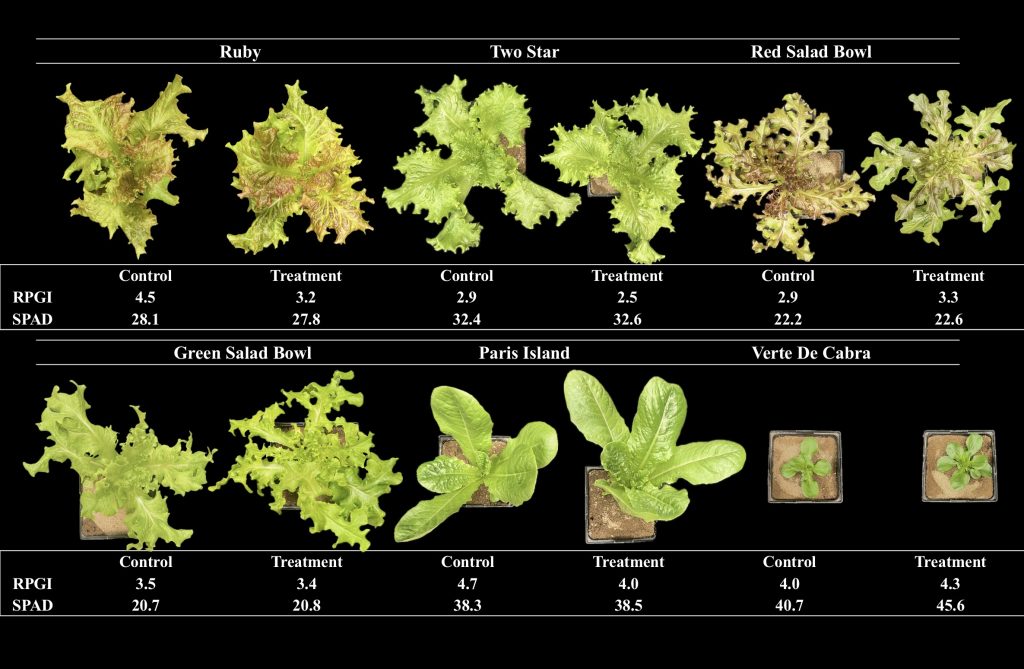

First, Hineman tested the performance of six different lettuce varieties, tracking the salinity levels, water retention, and plant growth of 96 potted lettuce plants throughout a 56-day trial.

Like the astronauts aboard the ISS, Hineman used the “pick-and-eat” harvest method for the lettuce plants, removing any leaves that were at least 10 centimeters in length 30 days after the lettuce seeds were sown. At 48 days post-sowing, leaves of at least 10 centimeters in length were harvested again; at 56 days, Hineman harvested the entire plant, in keeping with NASA protocol.

The plants were grown in calcined clay, a proxy for nutrient-deficient lunar soil. Currently, astronauts must transport soil from Earth to grow their lettuce, a practice that adds weight on their way into orbit. Eventually, astronauts may be able to collect lunar soil instead, so space-farming projects like Hineman’s often mimic the inhospitable growing conditions provided by lunar soil.

For each lettuce variety, a “control” group received fertilizer applications in similar amounts to those used by NASA astronauts. A second group of plants received larger amounts of fertilizer, introducing higher levels of mineral salts like sodium, magnesium, and calcium into the soil.

Hineman found that the group of plants that received more fertilizer also experienced higher salinity stress. In some varieties, plant growth even decreased with increased fertilizer application, indicating that the elevated salt levels limited growth.

In a second round of 56-day trials, Hineman is investigating whether inoculating lettuce plants with fungi can help mitigate the effects of increased salinity. As with her first set of experiments, the “control” group is receiving an amount of fertilizer similar to what’s currently used by astronauts while the “treatment” group receives more fertilizer.

In this experiment, Hineman inoculated emerging plants with two different types of powdered fungi. “When you water them, they will start to colonize on the roots,” she explains. “The fungi is supposed to basically eat the salt and give back to the plant so that it won’t be as salt-stressed and will also receive other nutrients.”

Throughout the trial, she’ll record salinity levels and plant growth to see if fungi colonization might be a viable method for reducing salt accumulation, improving plant health—and maybe even producing tastier lettuce in space.

Showcasing student success

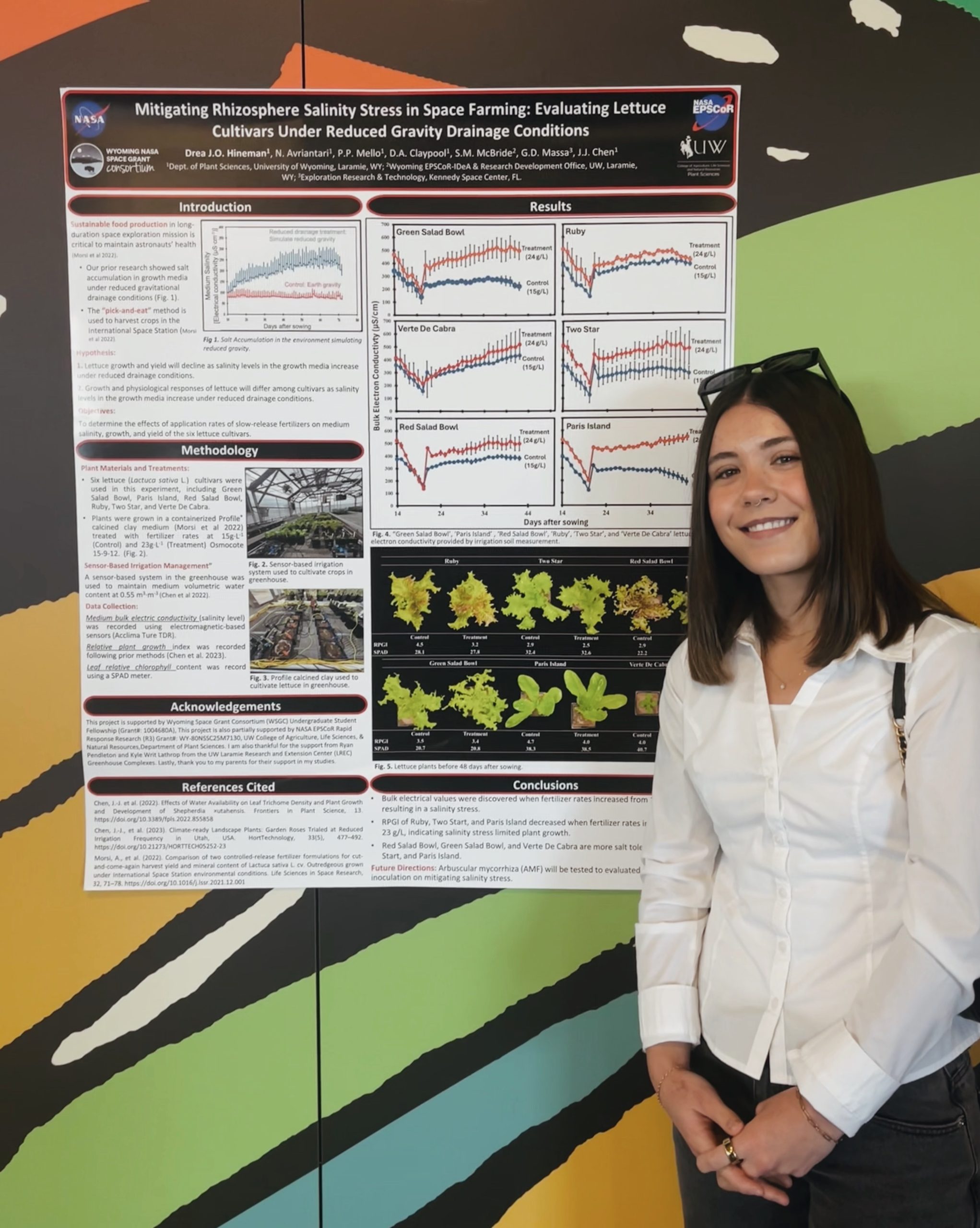

In October 2025, Hineman presented her research at a regional event in Boise, Idaho, organized by the educational nonprofit Spacepoint. The organization’s mission is to raise awareness of and encourage participation in the space industry, says founder and director Kyle Averill.

The recent Spacepoint symposium featured the theme “interplanetary life,” with the goal of sparking interest in careers related to the space industry. While open to the public, the event was designed with high school students, college students, and early-career professionals in mind.

Presentations and research posters, including Hineman’s, highlighted “examples of work, research, and development going on in the industry, from propulsion to food production…how to get there, how to survive, how to thrive,” Averill explains.

As a plant scientist, Hineman brought a unique perspective to the conference, introducing some participants to space farming for the first time.

That’s just what Spacepoint events are intended to do, Averill says—make the space industry accessible to a wider audience by connecting it to their interests on Earth.

“As the only agriculture major student invited to present at the conference, Drea effectively communicated to attendees from Washington, Idaho, Montana, and California that students can meaningfully contribute to science and space exploration,” says Chen. “I hope she can serve as a role model for future students.”

It was the first time Hineman had attended a professional conference and there was a lot to take in. Perhaps the most gratifying part of the experience, though, was a conversation with a middle school student. Hineman’s presentation was his favorite—even after listening to a professional astronaut speak. Not only was he fascinated by the concept of space farming, but he was also inspired by Hineman’s journey as a young scientist.

“When you think of Wyoming you don’t think, ‘Oh yeah, I can go to college and do a space-farming research project,’” Hineman reflects. “But my advice would be to figure out what your niche thing is, even if it’s something so small you don’t think other people are interested in it… Talk to professors that have the same motivation as you or have the same knowledge that you want to have to get where you want to be.”

Or, she says, grinning, there’s a simpler route: “Just go find JJ.”

To learn more about space-farming research projects conducted in Chen’s lab, contact him at jchen20@uwyo.edu.