For centuries, the migrations of massive herds of caribou defined the ecosystem and lifeways of people across the vast North American Arctic. New migration maps published on December 18 document a near complete collapse of one of the region’s formerly vast caribou migrations.

The new, detailed maps reveal the recent toll that human development and a myriad of pressures facing the Arctic have had on the long-distance movements of the Bathurst caribou, named for their historic calving grounds near Bathurst Inlet on the far northern coast of Canada. Researchers from the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) partnered with the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration, an international team of migration researchers headquartered at the University of Wyoming, to map how the caribou migration has been altered.

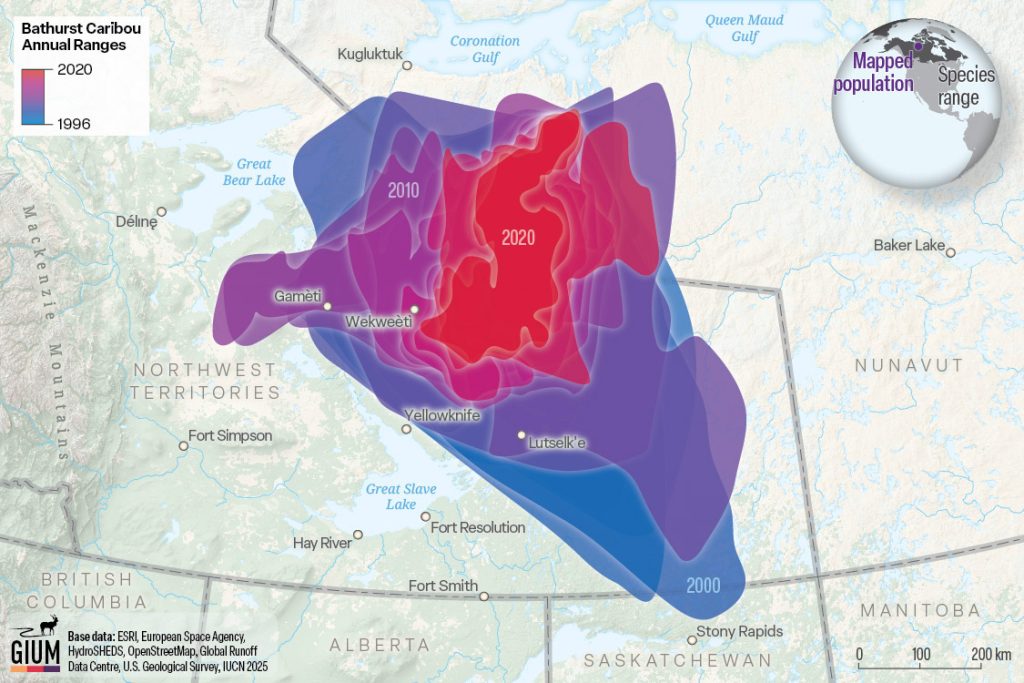

Abundant migratory caribou have made landscapes more productive, provided a prey base for the region’s carnivores, and shaped the culture of the Indigenous communities that have hunted them for countless generations. The Bathurst herd of barren-ground caribou once ranged from Nunavut all the way to northern Saskatchewan, with some individuals traveling over 300 miles on their yearly migrations.

Today, these migrations—and the large herds they sustain—are hanging in the balance. The Bathurst caribou population has declined from 400,000 to less than 4,000 over the last 30 years, according to new surveys by the government of the Northwest Territories.

“The steep decline of the Bathurst herd is not just a biological concern; it represents a profound cultural and ecological loss,” says Orna Phelan, wildlife biologist with the North Slave Metís Alliance, one of the Indigenous communities that stewards the caribou. “Conserving this herd means safeguarding our history, our identity, and the health of the land we all share.”

Published in the Atlas of Ungulate Migration, the maps document the dramatic reduction in the Bathurst caribou migrations and illustrate imminent threats from a proposed all-season road to connect current and potential mines to newly accessible deep-water ports, effectively bisecting the range. The maps also indicate where conservation efforts can yet prevent further disruption to this epic migration.

Wildlife scientist Elie Gurarie, at SUNY-ESF, a member of the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration who has studied the Bathurst caribou for the last 10 years, says the maps bring a renewed focus to the plight of the caribou.

“This project shows how interconnected and collaborative ecological science and conservation are in the Arctic,” Gurarie says. “Mapping the Bathurst caribou herd isn’t just about lines on a map; it’s about understanding a species whose vast habitats are beginning to fragment, the pressures from roads and mines, and the cultural and material significance these animals hold for Indigenous communities.”

The Atlas of Ungulate Migration represents a global effort to make migration maps publicly available for conservation and land-use planning. It is led by the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration working under the auspices of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, a United Nations treaty. The Bathurst herd is the first entry in the atlas for caribou, a circumpolar species facing an urgent conservation need.

Although many human communities benefit from the ecological and economic benefits of migratory ungulates, the caribou herds of the Arctic are one of the only wild, migratory ungulate populations in the world to which Indigenous communities still maintain strong traditional ties. The caribou are used for food and fiber and have shaped Indigenous cultures around the global Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. Their migrations are the longest known ungulate movements in North America.

The Bathurst herd is emblematic of the pressures facing migratory caribou worldwide, which have declined by 65 percent over the last 20-30 years. Rising temperatures due to climate change; an associated increase in insect harassment; poorer vegetation quality; and more frequent rain-on-snow events that make lichen, their primary winter food source, inaccessible under thick ice, increasingly stress the caribou populations.

These and other effects are compounded by the major impacts of expanding infrastructure. The new maps illustrate where the proposed all-season road—billed as the Arctic Security Corridor—will cut straight through the Bathurst’s core migration area, very near the herd’s calving grounds. This road will allow for expanded access and mineral exploration within the caribou’s migratory range and access to a deep-water port. Three diamond mines already operate within their range—in areas known to be preferred by the caribou. Indigenous stewards and researchers have documented large-scale caribou avoidance of these areas, as well as an almost complete impermeability of the winter ice roads that service the mines.

But tracking data and detailed maps, when used for planning, make it possible to develop in such a way as to not disrupt the seasonal migrations. If development happens in the right places and in the right ways, researchers believe it doesn’t have to spell the end of the Arctic’s caribou migrations. Indigenous-led guardians, harnessing traditional knowledge and boots-on-the-ground observations, are intensively monitoring traffic and caribou behavior on and around roads and mines.

Working in close partnership, Gurarie and colleagues are working to understand how the caribou are responding to various kinds and levels of disturbance, with an eye toward specific mitigation solutions that can make linear infrastructure more caribou-friendly.

Mapping approaches tested in Bathurst caribou range could have implications for the other large caribou herds that still inhabit the circumpolar North, perhaps allowing other regions to avoid stark population declines and to preserve the long-distance movements caribou require.

“Among all the caribou’s astonishing adaptations to not only survive, but thrive, in the Arctic, perhaps none is more important than the ability to move freely across large landscapes,” Gurarie says. “By working closely with First Nations, Inuit, territorial governments, and nongovernmental organizations, we’re not only documenting change, but also working on shaping solutions.”

About the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration

Headquartered at the University of Wyoming, the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration was created in 2020. The main aim of the initiative is to work collaboratively to create a global Atlas of Ungulate Migration (an inventory) using tracking data and expert knowledge; and stimulate research on drivers, mechanisms, threats, and conservation solutions common to ungulate migration worldwide. Initiative participants include global experts representing the world’s major terrestrial regions and most, if not all, of its longest migrations. The initiative seeks to spark conservation efforts worldwide by sharing and discussing new, ongoing, and proven approaches to maintain migration corridors across large landscapes. Visit the atlas at www.cms.int/gium.

This story was originally published on UW News.