Whether it’s in a security badge or livestock ear tag, you’ve probably encountered some form of RFID (radio frequency identification) technology. What you probably haven’t seen is a bumble bee wearing a tiny RFID “backpack” as it flits from flower to flower collecting pollen.

But that’s exactly what Sabrina White, a PhD student in the UW Department of Zoology and Physiology, plans to observe this summer at the Red Buttes Environmental Biology Laboratory outside Laramie. As part of her research on how Wyoming bumble bees respond to heat waves, she’s using RFID tags to track their movement in and out of hives.

Heat stress and foraging behavior

Unlike honeybees, bumble bees have an annual life cycle. Their colony lives for just one season; only the queen overwinters and emerges to start a new colony the next year. It’s one of the reasons they’re well suited to cold climates, including the mountains of Wyoming and even the Arctic.

Bumble bees can also air condition and heat their own colonies, fanning their wings to cool the hive and vibrating to stay warm. But as extreme weather events, including heat waves, become more common, how will these plucky little pollinators respond?

That’s the question driving White’s research. “I’m looking at sublethal temperatures that are realistically going to be experienced and how that affects foraging behavior and colony success,” she explains.

White has chosen to focus on Bombus huntii, a bumble bee commonly found in Laramie. “I want to use local bees because it’s important to understand how wild populations behave as opposed to using lab-reared colonies of non-native bees, which can’t be released here,” she says.

Bees with backpacks

Since even the smallest GPS units aren’t small enough for bumble bees, White settled for using RFID tags to track movement in and out of the hive. While the tags can’t track foraging paths, they can be used to record when bees enter and exit the hive.

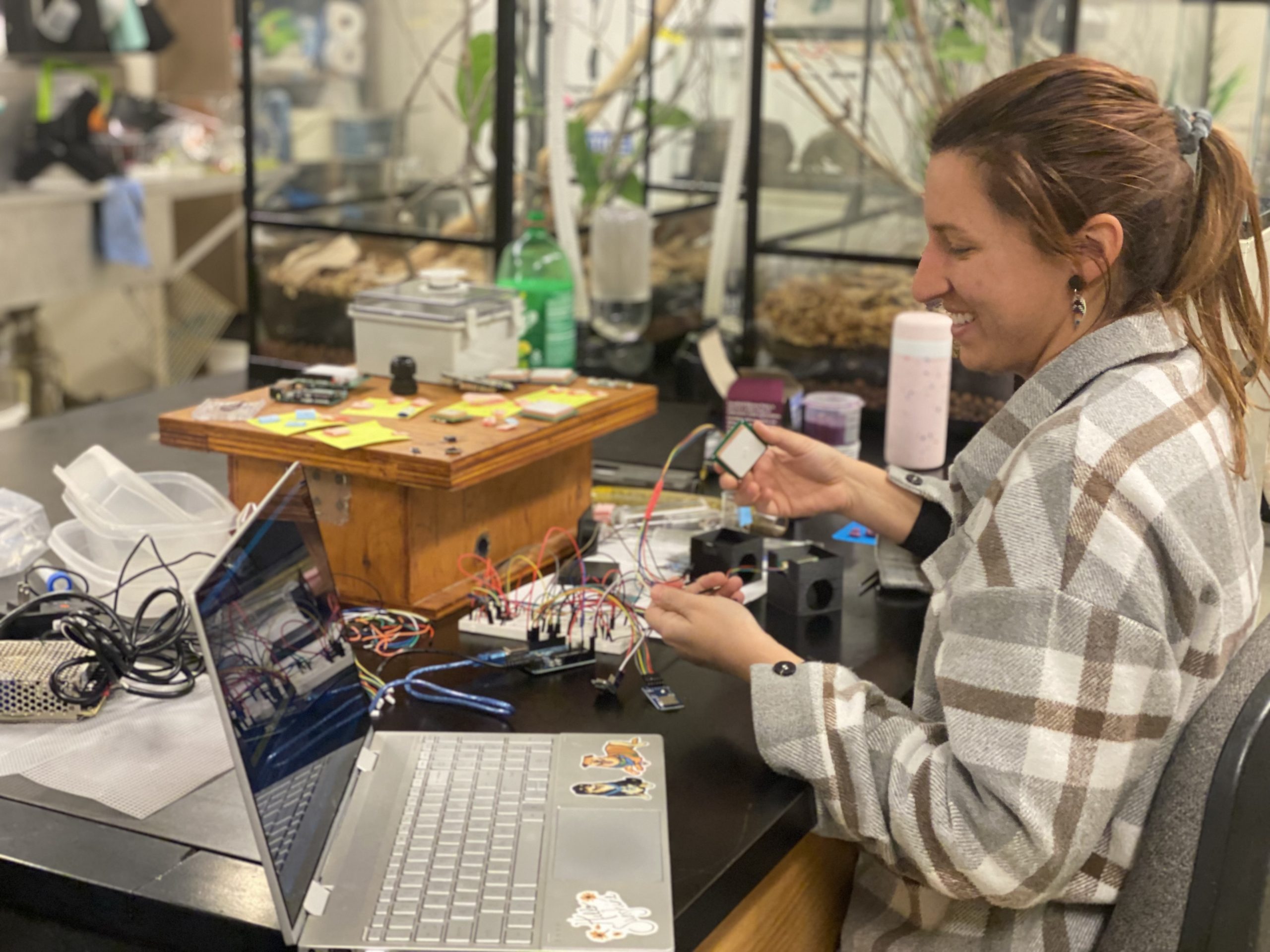

In order to record data, White must painstakingly glue 1.2-millimeter RFID “backpacks,” complete with tiny coiled antennas, onto each bee’s back. Unable to find premade antennas well suited to the task, White designed her own, hand-coiling and soldering them to each tag. This summer, she’ll tag 25 bees per hive for up to 50 hives (it currently takes about an hour to make 10 tags).

The tiny tags function like encoded license plates, says Steve Barrett, professor of electrical and computer engineering at UW. Data from these license plates is stored on an SD card in an Arduino microcontroller system.

“These are little bitty computers that are really inexpensive but very powerful,” Barrett explains. “Sabrina equipped the processor with an SD card, which is like giving a computer a hard drive. When a bee leaves, the time is logged, this data is put onto the hard drive, and when the bee comes back, data is captured again. It’s a great way to gather lots of data.”

Collaboration across colleges

When White ran into difficulties setting up the Arduino and RFID system, she reached out to Barrett to see if he could help, initiating an ongoing interdepartmental collaboration. Both Barrett and colleague Laura Oler, a lecturer in electrical and computer engineering, have worked closely with White to refine the circuit board and code required to run the system.

Not only has the collaborative effort helped take White’s data collection system to the next level, it’s also led to new opportunities for undergraduates in UW’s engineering program. One of these students designed a system that delivers electricity to the hives at the Red Buttes lab, including an alert system that notifies White if the power goes out.

Barrett and Oler are excited to continue forging partnerships with researchers in other colleges. “It’s great to have projects where we can contribute our expertise to a problem and make something useful for somebody’s research,” Oler comments. “We would love to find more collaborations where we could do these kinds of things.”

Tracking behavior in the wild

After the trial run last year, White looks forward to starting the first of four seasons of data collection. In the spring, she’ll catch emerging queen bees in Laramie and nurture them at ACRES Student Farm until they’re ready to begin building a colony. Later in the season, after the colony has been transported to Red Buttes and the worker bees are large enough to easily transport their RFID backpacks, White will tag a random subset of workers.

Bees undergoing experimental treatment will be exposed to a hot water bath at a set temperature for 45 minutes, which is the average length of a foraging trip. This process simulates a foraging trip during a heat wave. The behavior of the treated bees will be compared to that of control bees who were removed from the hive for 45 minutes but not exposed to the water bath.

While the simulated heat waves are below lethal temperatures, White predicts they may affect how much pollen and nectar foragers bring back to the colony. “I’m expecting them to potentially forage less, maybe doing fewer foraging trips or bringing back less resources from those trips,” she says. “Hopefully they can compensate and the colonies do fine. But it’s still important to know how bee colonies can be affected by changing climate. If we know that, we might be able to predict how populations will change in the future.”

To learn more, contact faculty advisor Michael Dillon at michael.dillon@uwyo.edu.

This article was originally published in the 2024 issue of Reflections, the annual research magazine published by the UW College of Agriculture, Life Sciences and Natural Resources.