For many Wyoming visitors and residents, winter isn’t just snow season—it’s also snowmobiling season.

This type of seasonal recreation can be an important source of economic activity, especially in the state’s small rural communities. Snowmobilers rent rooms at local hotels, eat at local restaurants, and purchase fuel and supplies at local stores.

But what happens if there’s not enough snow to ride? And, on the flip side, how might rural communities benefit if they consistently receive more snow?

Economic impacts of winter recreation

Every 10 years, the Wyoming State Trails Program works with UW to collect economic data associated with snowmobile and off-road vehicle (ORV) use on public land. In 2023, a group of researchers in the UW Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics partnered with atmospheric scientist Bart Geerts and his team1 to take the investigation a bit further.

“I wanted to figure out how future changes in climate may change how we go about economic development and tourism in the state,” says Anders Van Sandt, community development specialist in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics.

“Tourism is one of the top three industries in Wyoming and winter tourism tends to be really seasonal,” he continues. “The more you can extend the season or add on in different seasons to retain employment means keeping jobs in rural communities.”

In collaboration with fellow agricultural economics professor Chris Bastian and graduate student Kelsey Lensegrav, Van Sandt used survey data and climate predictions to examine how changes in snowpack could affect Wyoming’s economy.

Correlating snow depth and spending

Surveys were sent to randomly selected resident and non-resident snowmobilers who registered with the Wyoming State Trails Program. Respondents were asked about their preferred snowmobiling sites, how much they spent on snowmobiling equipment and travel, and what impacted their enjoyment of snowmobiling (e.g., preferences for certain types of trails) during Wyoming’s 2020–2021 snowmobiling season.

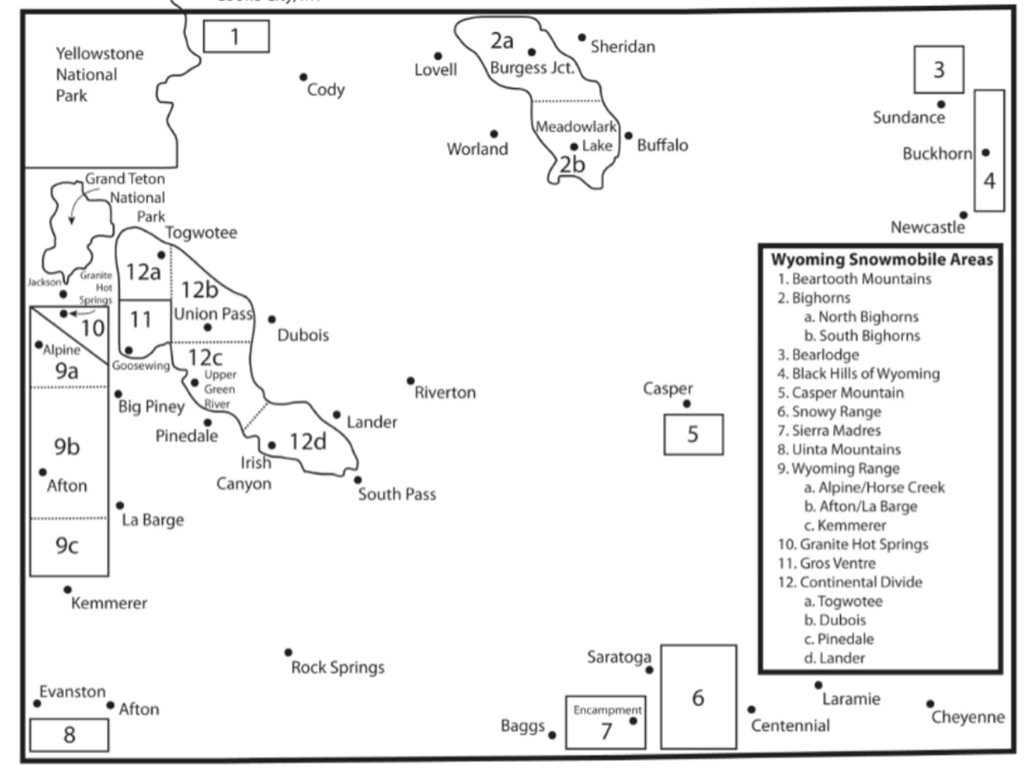

Based on survey results, the researchers developed economic models to predict how changes in snow depth could affect snowmobiler spending at 18 sites across Wyoming. To cover a wide variety of scenarios, they used nine different climate models with varying predictions for mid-century and end-of-century snow depth. Entering different snow depths into their economic model, they generated predictions about how snowmobiler activity might influence local economies in each set of conditions.

Residents and non-residents

In this study, snowmobiler behavior and spending were broken down into two categories: resident and non-resident. Results suggested a clear divide in the predicted behavior and spending patterns of residents versus non-residents.

In nearly all mid-century and end-of-century predictions, the number of non-resident trips and value of non-resident expenditures were predicted to increase relative to the 2020–2021 baseline. Meanwhile, snowmobiling trips and expenditures associated with Wyoming residents were expected to decline.

Overall, this pattern could potentially benefit Wyoming’s economy at a statewide level. While resident snowmobiling brings economic activity to rural communities, it represents movement within the state’s economy. Non-resident spending, on the other hand, introduces new dollars into the state.

The current and predicted decline in resident registrations doesn’t necessarily mean a decline in trail use, Van Sandt notes. Locals may be more inclined to buy tracks for their ORVs rather than owning both snowmobiles and ORVs, for example.

Gains and losses

Although Wyoming’s non-resident snowmobiling industry is likely to grow at a statewide level despite changing snow depth, models suggest that economic impacts will vary by community. “Given the models the climate scientists established, we found that there are sites that gained and some that decreased in snow,” says Bastian.

Based on mid-century and end-of-century climate predictions, 5 to 6 of the 18 study sites were deemed unlikely to maintain the recommended 8 inches of snow during the snowmobiling season. Unsurprisingly, those sites will likely experience reduced demand and snowmobiler spending.

Results also suggested that sites predicted to receive more snow could benefit economically from changing environmental conditions. The Snowy Range, for example, is expected to experience increases in both snow depth and non-resident snowmobiling expenditures.

While the study indicated that some Wyoming snowmobiling sites may suffer economically from reduced snowpack, the state’s altitude may help it outperform neighboring states like Montana and Idaho.

“Our estimates may actually be conservative in the sense that we focused just on the state of Wyoming,” Bastian explains. “A number of the states surrounding us are probably going to experience net loss and Wyoming is generally predicted to be a net gainer in some high-elevation sites. So, we may see a higher influx into the state from non-residents than we captured in this study.”

Planning ahead

Bastian and Van Sandt are hopeful that their research will positively contribute to trail management and economic planning in communities that serve as “gateways” to outdoor recreation opportunities.

For some communities, that might mean pivoting to focus on other types of outdoor recreation. “For places that will likely lose snowpack, there may be some recreation substitution,” Bastian comments. With less snow, perhaps a longer ORV season will help compensate for the loss of snowmobiler spending, he suggests. In other locations, maybe the market for cross-country skiers will expand even if the snow depth can no longer support snowmobiling.

Regardless, the circumstances and response will vary by community. While some local economies may grow in response to increased demand for snowmobiling-related amenities, other communities may shrink as residents migrate elsewhere to find work.

“We can provide information that’s relevant, but the communities are the ones who come up with ideas on what to do next,” Van Sandt notes. “If they have this information ahead of time, they may have a better chance of transitioning to a slightly different-looking economy in the future.”

To learn more, contact Bastian at bastian@uwyo.edu.

This article was originally published in the 2024 issue of Reflections, the annual research magazine published by the UW College of Agriculture, Life Sciences and Natural Resources.