People tend to underestimate Wyoming.

As the least populated state, expectations seem to be Wyoming’s contribution to the country is as limited as the households on our census.

Anyone who knows Wyoming knows this isn’t true. Especially important to those interested in sustainable livestock production, we are one of the key players in the U.S. sheep industry.

Like the Wyoming assumption, trace nutrients importance, specifically zinc, for sheep tends to be underestimated. Larger scale operations and larger scale ambitions for the sheep industry as a whole require more and more acutely refined precision management, even down to trace nutrients.

Low input – High output

Low input – High output

Zinc is an essential micro-nutrient to sheep production. Wyoming produces high-quality sheep off the back of a rugged landscape. The physiologically challenging timepoints of breeding, pregnancy, and lactation on the sheep production calendar (fall-winter) occur when rangeland forages are at their lowest nutritional quality.

While Wyoming’s output of meat and wool has been impressive, there is room for improvement. Sheep are being selected for greater productivity, but the recommendations specific to certain nutrients haven’t kept pace. Reviving and refreshing previously discovered insights can help enrich and enlighten today’s practices.

Zinc and modern production

Scientists in the 1930s discovered zinc was essential for sheep production. The element is the second most abundant trace mineral in the body with important functions in:

- gene expression,

- immune function,

- reproduction,

- appetite regulation, and

- wool production.

Unlike other minerals, zinc is stored in the body in only small amounts and needs to be supplied continuously.

The zinc content of grazing diets is adequate in early summer in most cases, but in later months, zinc levels decline to inadequate concentrations. This results in suboptimal performance, especially during the most physiologically demanding times of breeding and pregnancy.

A national forage survey conducted by USDA National Animal Health Monitoring System in 1993 found 63 percent of native grasses failed to meet dietary zinc requirements for sheep. Supplying additional zinc is a best practice to alleviate these seasonal shortfalls and demanding production periods; however, ensuring zinc consumption on extensive landscapes can be sporadic and as a result, some producers opt not to provide the mineral during certain times of the year.

Complicating the present-day picture is that previously recommended zinc supplementation levels may be inadequate for the optimal performance of modern-day sheep. “Modern-day sheep” might be a bit vague for those of us who don’t eat, breathe, and speak ruminant, so here are a few statistics:

Over the past 50 years, fine-wool Wyoming sheep have achieved selection milestones including 50 percent greater growth rates, 30 percent greater mature body size, and as a result 25 percent increases in clean wool production.

USDA data suggests that twin-bearing capacity has increased in the U.S. sheep flock since 1930.

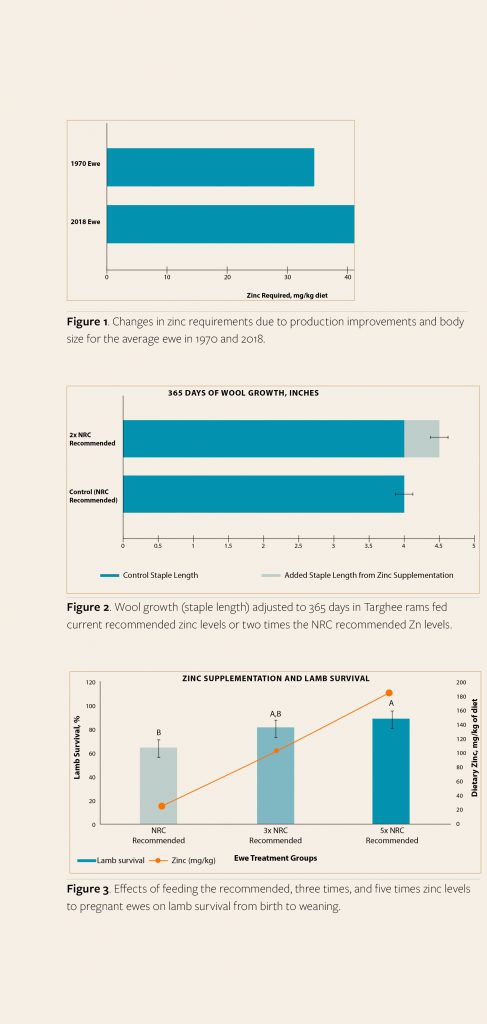

Estimated zinc requirements need to increase from 34 milligrams/kilogram to and estimated 57 mg/kg, or 67 percent for the average ewe (Figure 1). Our goals for production have changed, sheep have changed, and recommending nutritional changes is important, too.

The right amount of zinc can pay dividends

Current research evaluates whether feed supplements contain adequate levels for the best health and well-being of sheep, in addition to comparing different chemical forms of zinc in sheep diets.

Recently completed research in 2017-2018 found rams grew 14 percent longer wool when fed double the recommended levels of zinc, resulting in more pounds of wool (Figure 2). Considering the record high wool prices in 2018, this increase in production can increase margins.

Agriculture in America thrives or dies on the margins. These same rams fed increasing levels of zinc also had greater feed conversion efficiency; they grew more with less feed when compared to rams eating the current recommended levels, benefitting the sustainability of the producers and the environments in which they produce.

Zinc benefits extend beyond the ram. In a separate study conducted at the University of Wyoming, pregnant sheep were fed increasing levels of zinc. This resulted in a 40 percent increase in lamb survival from birth to weaning (Figure 3). Relatedly, collaborative work between Montana State University, UW, and the USDA Sheep Experiment Station in Dubois, Idaho, concluded ewes with lower zinc levels were associated with sub-clinical (difficult to visually detect) mastitis producing 33 fewer pounds of lamb (and $52 less) than those with healthy udders.

Current research is examining whether greater zinc levels fed throughout pregnancy can reduce the incidence of bacterial infections of the udder, preventing lost production potential. Research from our group has found 20 percent of ewes in a flock suffer from sub-clinical bacterial infections of the udder. This intervention could save the average 400-head producer over $4,000 a year.

There is still work to do in understanding the optimum levels of zinc in sheep diets. For example, understanding breed differences that may require additional zinc levels is an important delineation.

We are trying to more closely tailor zinc requirements to the type of sheep Wyoming raises. So far, we’ve discovered breed differences exist in how much zinc is transferred to the newborn lamb. Fine-wool lambs have greater zinc concentrations at birth than meat breeds. The chemical form of zinc (zinc sulfate vs. zinc amino acid complex) has shown to have differential effects on the rumen bacteria and subsequent performance of the animal. Determining what chemical forms should be utilized, and at what ratio of zinc sulfate to zinc amino acid complex in a mineral, is a focus of future efforts.

Finally, and most important to tailoring a custom mineral for sheep ranches scattered throughout Wyoming, is understanding the trace mineral composition of the plants sheep consume at different times of the year. What are the differences in grass, forb, and shrub species, and how much zinc is actually available at different stages of plant maturity?

Efforts are under way to sample sheep ranches throughout Wyoming to identify trace mineral deficiencies and help producers assess where their forage resources might be falling short for a particular trace mineral. Conducting applied research that helps the Wyoming sheep producer while advancing knowledge in the field is a guiding principle behind these efforts.

Private industry-public institution partnerships

Private industry-public institution partnerships

The next step in supporting the modern-day sheep is communicating research results to feed companies marketing products throughout Wyoming and surrounding regions. Leveraging the extension arm of the land-grant university pipeline, we’ll continue to communicate translational research to industry partners and invite them to revisit their sheep mineral products.

Providing timely information to private industry also involves synthesizing late-breaking research into translational information that enhances decision making. Feed companies have repeated time and again their reliance on land-grant universities to generate the data that drives their decision-making.

In an era with fewer sheep research and extension programs we, as ever, are happy to oblige.

Authors: Whit Stewart, Assistant Professor, Department of Animal Science, Extension Sheep Specialist. Chad Page, Ph.D. student, Department of Animal Science.

To contact: Stewart can be reached at (307) 766-5374 or whit.stewart@uwyo.edu.