From tracking migratory mule deer and sagebrush sparrows to monitoring cutthroat trout populations, the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit conducts research with a purpose. For faculty and students in this research group, scientific inquiry is directly guided by questions and concerns raised by wildlife and fisheries managers in Wyoming.

The unit’s mission is twofold: 1) to conduct rigorous applied research that serves the needs of Wyoming’s current wildlife managers and 2) to nurture the next generation of wildlife managers.

Unit faculty and graduate students work closely with state and federal agencies, including the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and Wyoming Parks Department.

“They come to us with an issue they want to address, and we develop a project, recruit and train students, and gather the information the state needs to better manage that species,” explains Matt Kauffman, unit leader and professor of zoology and physiology.

The Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit is a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) program but also functions as part of the UW Department of Zoology and Physiology, now housed in the College of Agriculture, Life Sciences, and Natural Resources. More than a third of zoology and physiology graduate students conduct research in the unit.

“We’re training the wildlife managers of the next generation,” says Kauffman. “Our graduate students get instruction and guidance from their graduate committee here on campus, but they also get real on-the-ground training and perspectives from the wildlife managers they work with.”

The Kauffman Lab: Mule deer migration and more

Kauffman’s research focuses primarily on migration, especially that of mule deer and other ungulates. A co-founder of the Wyoming Migration Initiative, he is currently leading a long-term study on the whys and hows of ungulate migration in Wyoming.

His group seeks to better understand the benefits of migration and how migration patterns are learned, especially as seasonal routes are increasingly impacted by human development. Currently, Kauffman’s team is tracking mule deer that migrate long, medium, and short distances, using mortality and nutrition data to evaluate how these migrations influence herd survival and health.

In a study of mule deer migrations from the Red Desert to Hoback, the researchers found that the deer were quite faithful to their annual routes. Long-term measurements of fat gain, reproduction, and overwinter survival suggested that herds completing this long-distance migration have a much higher rate of population growth than deer remaining in the Red Desert year-round.

“Another major effort by my group is to understand how animals learn to migrate,” Kauffman notes. “The assumption is that they learn from their mothers, but we’ve never been able to test that because it’s very hard to track young animals.”

Kauffman’s team is using GPS collars to track female mule deer, elk, and moose, as well as their young. Over the next couple years, they’ll use this data to understand whether the young animals inherit and follow the migration patterns of their mothers.

Kauffman also leads the national Corridor Mapping Team (CMT), a USGS-funded collaboration between state, federal, and tribal partners. Since releasing its first reports in 2020, the CMT has mapped the migrations and seasonal ranges of 218 unique ungulate herds in the western U.S. To learn more, contact Kauffman at mkauffm1@uwyo.edu.

The Walters Lab: Understanding Wyoming’s native fish

Annika Walters, associate professor of zoology and physiology, leads the unit’s applied fisheries ecology program, focusing primarily on native fish conservation. Walters frequently conducts research on the cutthroat trout, Wyoming’s primary native sport fish. Her team is currently assessing the best ways to monitor trout populations and the relative importance of different habitat types, among other topics.

Her group also studies how drought, human activity, and other disturbances affect native fish populations. By observing how fish respond to these stressors, the Walters lab provides managers with data they can use to help mitigate the effects of environmental changes.

Walters and her students often conduct localized studies that help inform management decisions in specific locations. In some cases, that might mean assessing options to relocate populations of a species of conservation concern. In other cases, Walters’ group might monitor how stocking fish affects existing aquatic communities over time or observe how fish evolve in a closed environment like an alpine lake.

Sometimes these projects require considerable sleuthing, using both historical records and genetic analysis. For example, Walters is currently working with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department and colleague Catherine Wagner to assess Yellowstone cutthroat trout stocking history and identify unique genetic populations.

While Walters’ primary research focus is on native fish, she also studies amphibians like boreal toads. Amphibians are declining at a greater rate than any other invertebrate in the world, she notes, and it’s important to understand how they’re adapting—or not adapting—to changing environmental conditions.

In a recent study, Walters and colleague Anna Chalfoun found that toads suffering from a fungal infection tended to favor more exposed habitats, selecting hotter, drier locations over the cool, moist, protected habitats they usually prefer. This behavior may be a form of self medication to prevent the fungi from flourishing, Walters explains, and may offer insight into toad survival.

To learn more, contact Walters at annika.walters@uwyo.edu.

The Chalfoun Lab: Looking out for sensitive non-game species

Associate professor and assistant unit leader Anna Chalfoun studies wildlife-habitat relationships in western songbirds and other non-game species. Her research is guided by the following questions: Why do animals choose the habitats they do, and how well do they survive and reproduce in those habitats? What happens when humans alter those habitats?

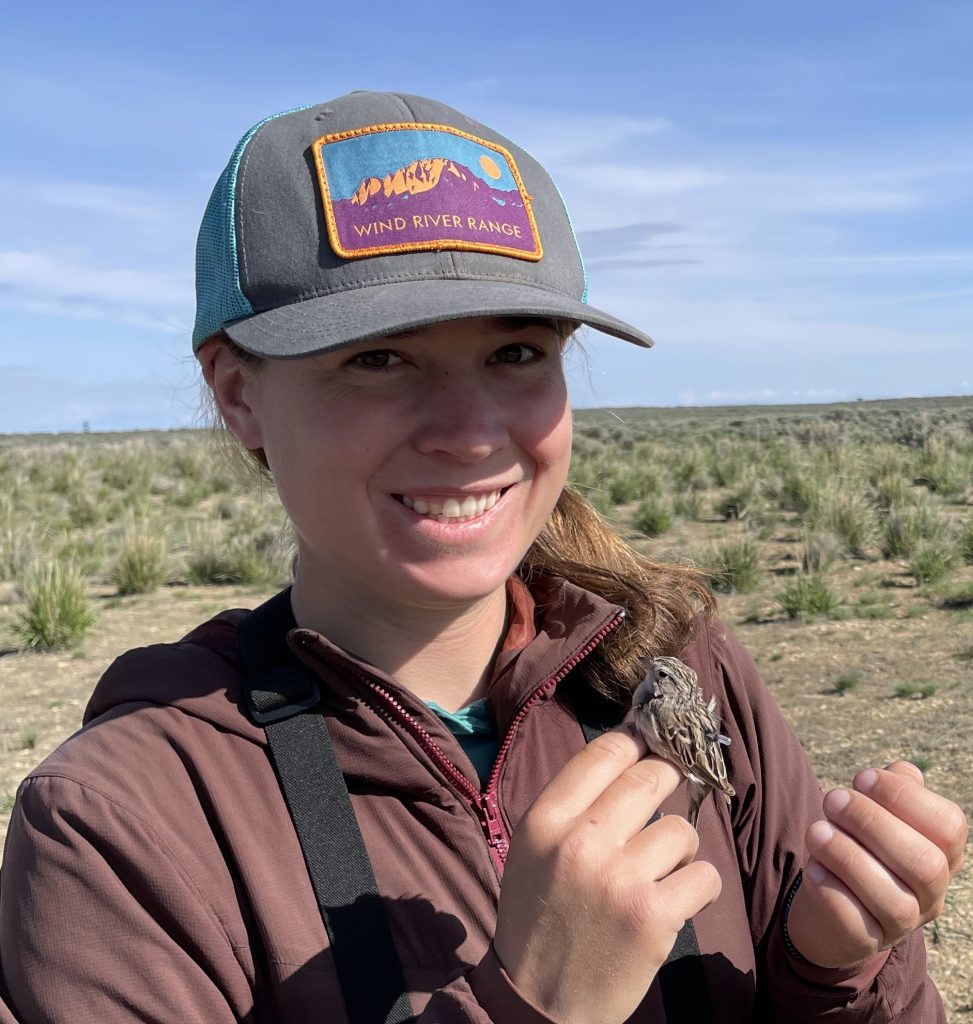

Many of Chalfoun’s research projects address what’s known as human-induced rapid environmental change (HIREC). Currently she is leading a long-term project investigating how energy development in western Wyoming affects three declining songbird species that rely on sagebrush habitats. Specifically, she’s monitoring the survival and reproductive rates of the sagebrush sparrow, Brewer’s sparrow, and sage thrasher. Her group has helped identify areas where these species tend to have the highest reproductive success as well as providing insight into how natural gas development affects the birds.

Chalfoun and her students also recently expanded the study to track migration routes and determine whether individuals return to the same nesting sites in Wyoming. “Now we’re trying to better understand survival rates are, and what factors influence return to the same breeding sites,” she explains.

Chalfoun frequently works with animals identified by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s State Wildlife Action Plan as species of greatest conservation need (SGCN). “My task is to help provide information on sensitive non-game species that our state and federal cooperators have deemed may be at risk,” she says. In addition to songbirds, these animals may include amphibians, reptiles, raptors (hawks, eagles, and owls), and small mammals like the American pika and pygmy rabbit.

For example, Chalfoun’s group recently collaborated with the Wyoming Natural Diversity Database (WYNDD) to study the habitat preferences of the northern long-eared bat. Their research showed that female bats preferred different types of roosting sites depending on factors such as whether they had pups or were lactating. Ultimately, this work has implications for forest management in sites suitable for maternal roosting.

To learn more, contact Chalfoun at achalfou@uwyo.edu.

This article was originally published in the 2024 issue of Reflections, the annual research magazine published by the UW College of Agriculture, Life Sciences and Natural Resources.